Changing History to HERstory: Freedom Fighters and Faithkeepers

Kat Shaw conceived her 'Changing History to HERstory' exhibition to mark International Women's Day 2021. The exhibition celebrated the lives of 57 amazing women from a range of backgrounds; women who, in ways large or small, have made their mark. To read the stories of all of Kat's HERstory muses (visual artists, scientists and explorers, stars of sport and more), follow the links on the exhibition's homepage.

This page focuses on the Freedom Fighters and Faithkeepers whose bravery and willingness to push boundaries inspired Kat's art.

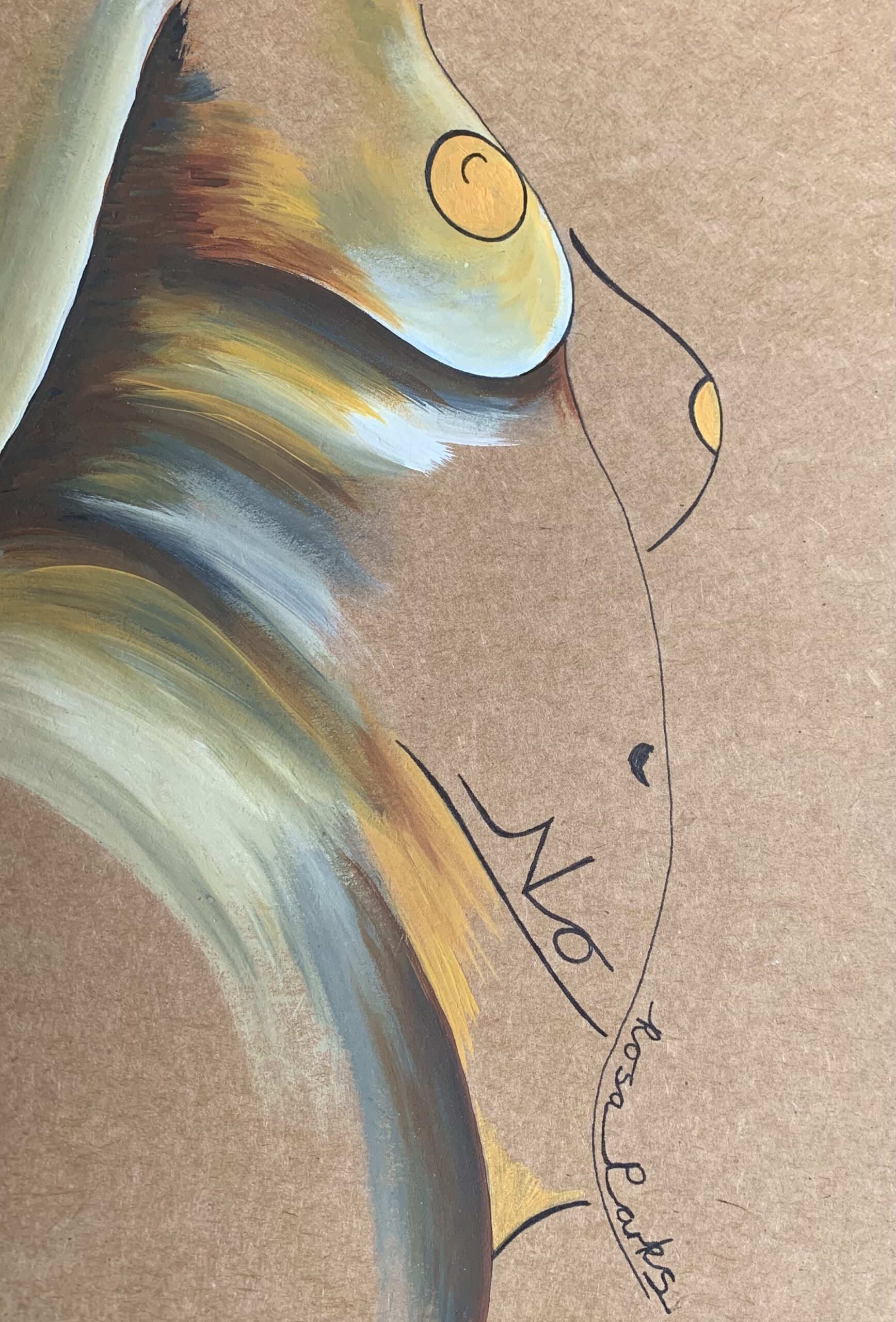

Rosa Parks

Rosa Louise McCauley was born in 1913 in Tuskegee, Alabama. She attended an industrial school for girls and later enrolled at Alabama State Teachers College for Negroes (now Alabama State University). Unfortunately, she was forced to leave to take care of her ailing grandmother.

Rosa was a big supporter of the Civil Rights Movement from a young age, and when she married local barber Raymond Parks at 19, she became even more involved in the cause. He was actively fighting to end racial injustice and they worked with many social justice organisations. Rosa was elected secretary of the Montgomery chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Rosa's famous refusal to move to the bus seats designated for 'coloureds' is often portrayed as a spur-of-the-moment act, but it was not; it was a planned act of resistance, as was the subsequent Montogomery Bus Boycott. Rosa, was, by this point (1955) very much a leader and organiser of civil rights campaigning and action in Alabama. her actions sparked protests against segregation in many other parts of the US.

The Parks moved to Virginia, then Detroit, where she was an invaluable and active member of several organisations working to end inequality. However, by 1980, Parks was exhausted, widowed, and in financial trouble after donating all her time and money to the cause, and she was also in poor health. She was only saved from eviction by local churches and community members

She died on 24th October 2005, at the age of 92. The United States Congress has called her 'the first lady of civil rights', 'the mother of the freedom movement' and 'the woman who stood up for herself and others by sitting down.'

“No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.”

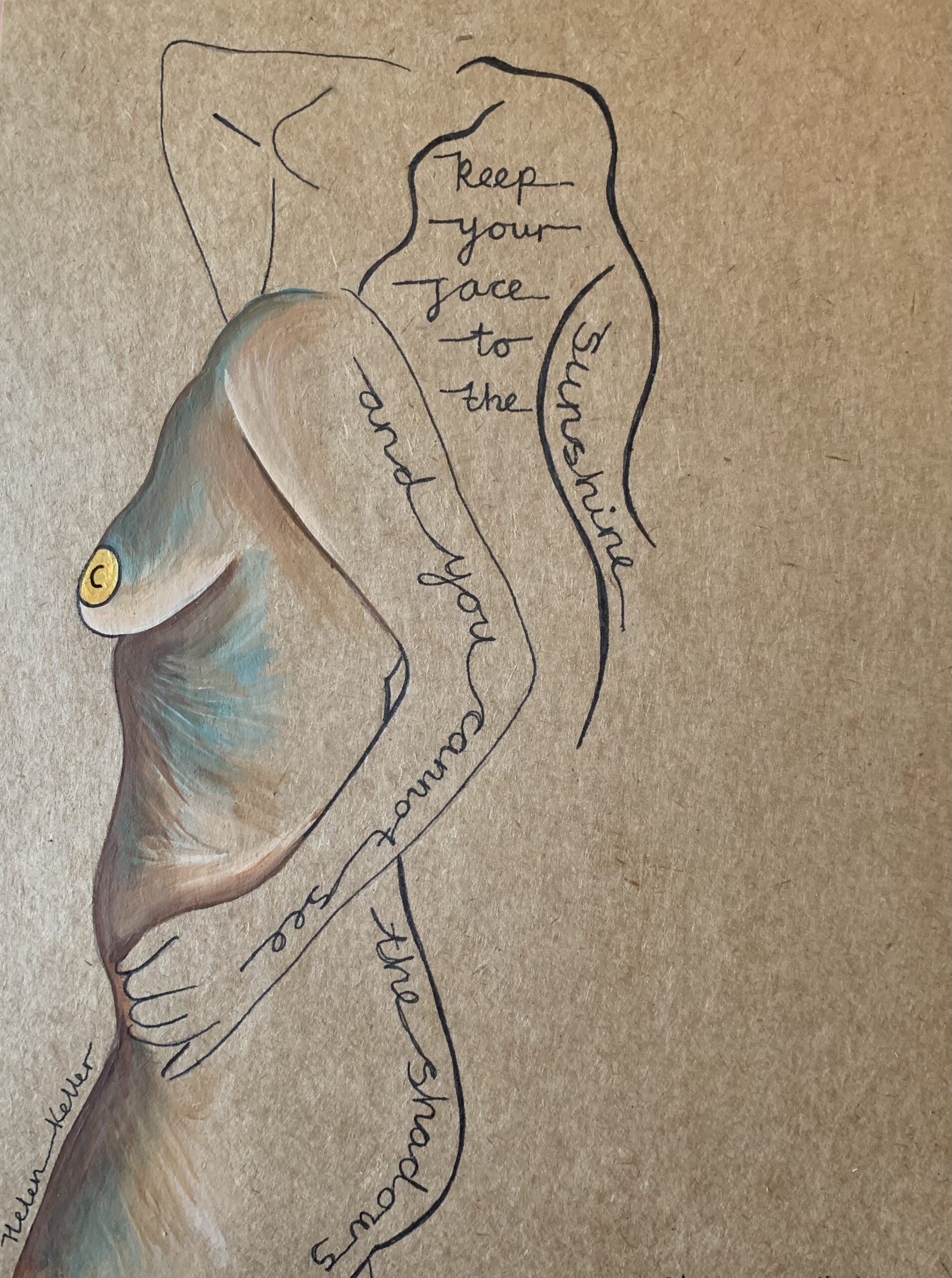

“Keep your face to the sunshine and you cannot see the shadows.”

Helen Keller

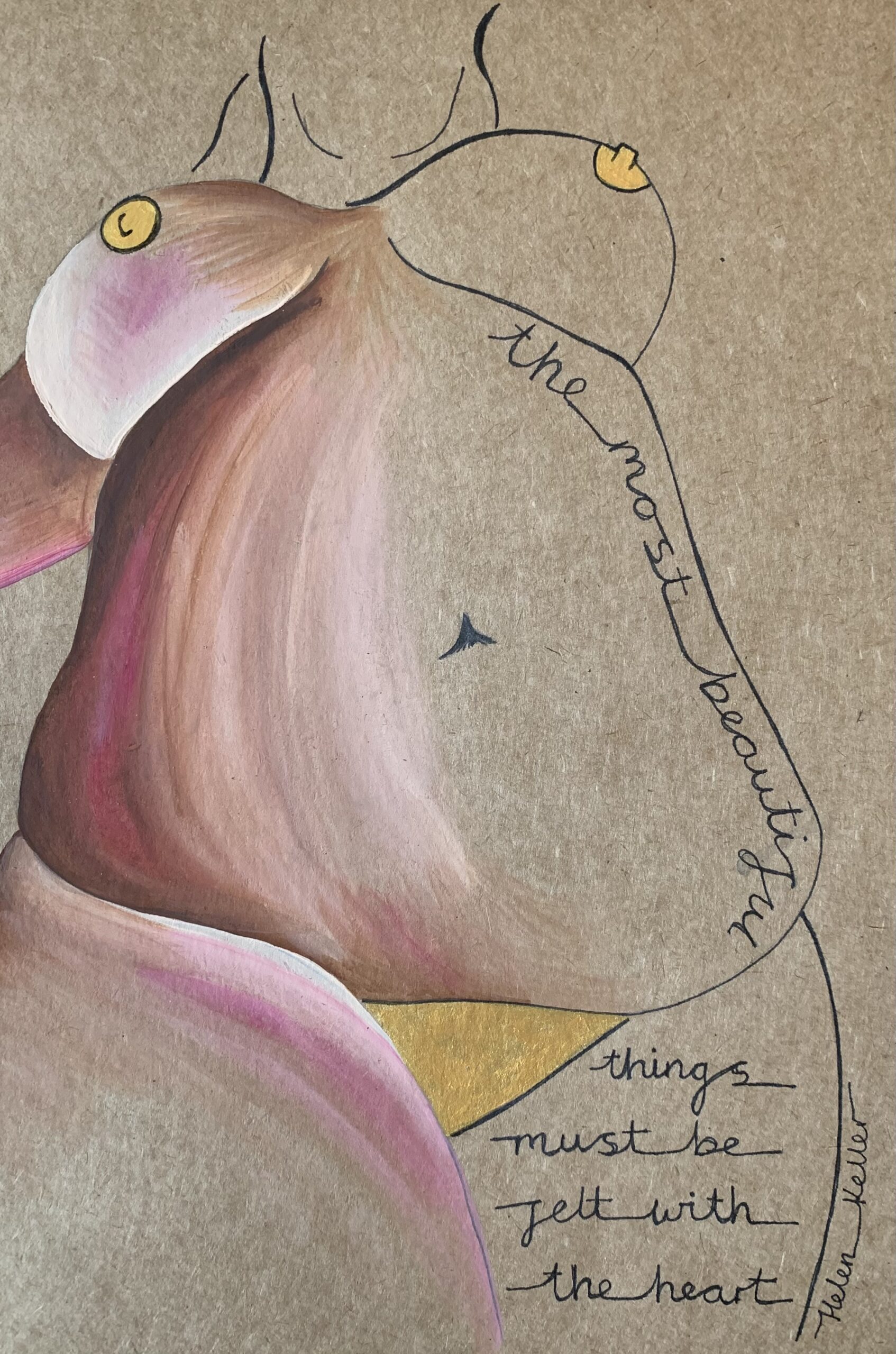

The best and most beautiful things in the world cannot be seen or even touched – they must be felt with the heart.”

Helen Keller was born in Alabama in 1880. A serious illness (possibly scarlet fever or meningitis) robbed Keller of her speech before she turned two. However, she learned to communicate by feeling her family’s faces and developed her own limited sign language with Martha Washington, the cook’s daughter.

At first, she had no formal education, but her mother recognised her intelligence. Having read of inventor Alexander Graham Bell’s work with deaf children in a Charles Dickens’ travelogue, she sought Bell’s advice. Keller was six when Bell referred her to Anne Sullivan, a 20-year-old graduate of the Perkins School for the Blind (run by Bell’s son-in-law).

“The most beautiful things... must be felt with the heart.”

So began the remarkable progress of Helen Keller, under a teacher who has also become legendary. With Sullivan’s help (and discipline, which she sorely needed!), she quickly learned to recognise letters and words signed into her palm. Sullivan took her to the Perkins School to learn to read and write Braille (with the aid of a Braille typewriter) and to the Horace Mann School for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing in Boston to learn speech. Keller also learned to read the lips and throats of speakers by touch.

Her teenage years were spent first at the Wright-Humason School for the Deaf in New York City, then the Cambridge School for Young Ladies in Massachusetts. She went on to Radcliffe College in 1900, achieving a Bachelor of Arts degree cum laude in 1904–becoming the first deafblind person to do so. During her time at college, Keller published her first two books with Sullivan’s help: The Story of My Life (1902) and Optimism (1903), establishing her as a writer and then a lecturer. Her articles on blindness helped break the taboo on the subject, particularly in women’s magazines, due to its connection to venereal disease.

Her move into lifelong political and social activism, though, happened after she moved in with Sullivan and her new husband, social critic and Harvard lecturer John Macy in 1905. Keller supported suffrage and socialism, advocated for the blind and deaf, and supported pacifism during World War I. In 1915, she co-founded the American Foundation for Overseas Blind to support World War I veterans blinded in combat. This organisation later became Helen Keller International, expanding its mission to tackle blindness, malnutrition and poor health. Five years later, she co-founded the American Civil Liberties Union.

She began to support the American Federation for the Blind after its establishment in 1921, and after becoming a member in 1924, she participated in numerous campaigns to raise awareness and donations. Her efforts to improve the treatment of the deaf and the blind were instrumental in changing attitudes to the disabled, who were often sent to asylums, and in the organisation of commissions for the blind. After Sullivan died in 1936, Keller continued to lecture internationally and write. She visited 39 countries on five continents between 1939 and 1957, including tours of military hospitals in World War II and visits on behalf of the American Foundation for Overseas Blind.

Helen Keller was the subject of numerous books, TV shows and films, both during her life and after, and in 1956 she won an Academy Award for a documentary film about her life. However, in 1961 she suffered a stroke that caused her to retire from public life. She was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1964 by President Lyndon Johnson and received numerous other accolades and honorary degrees in her lifetime. She died in Connecticut in 1968.

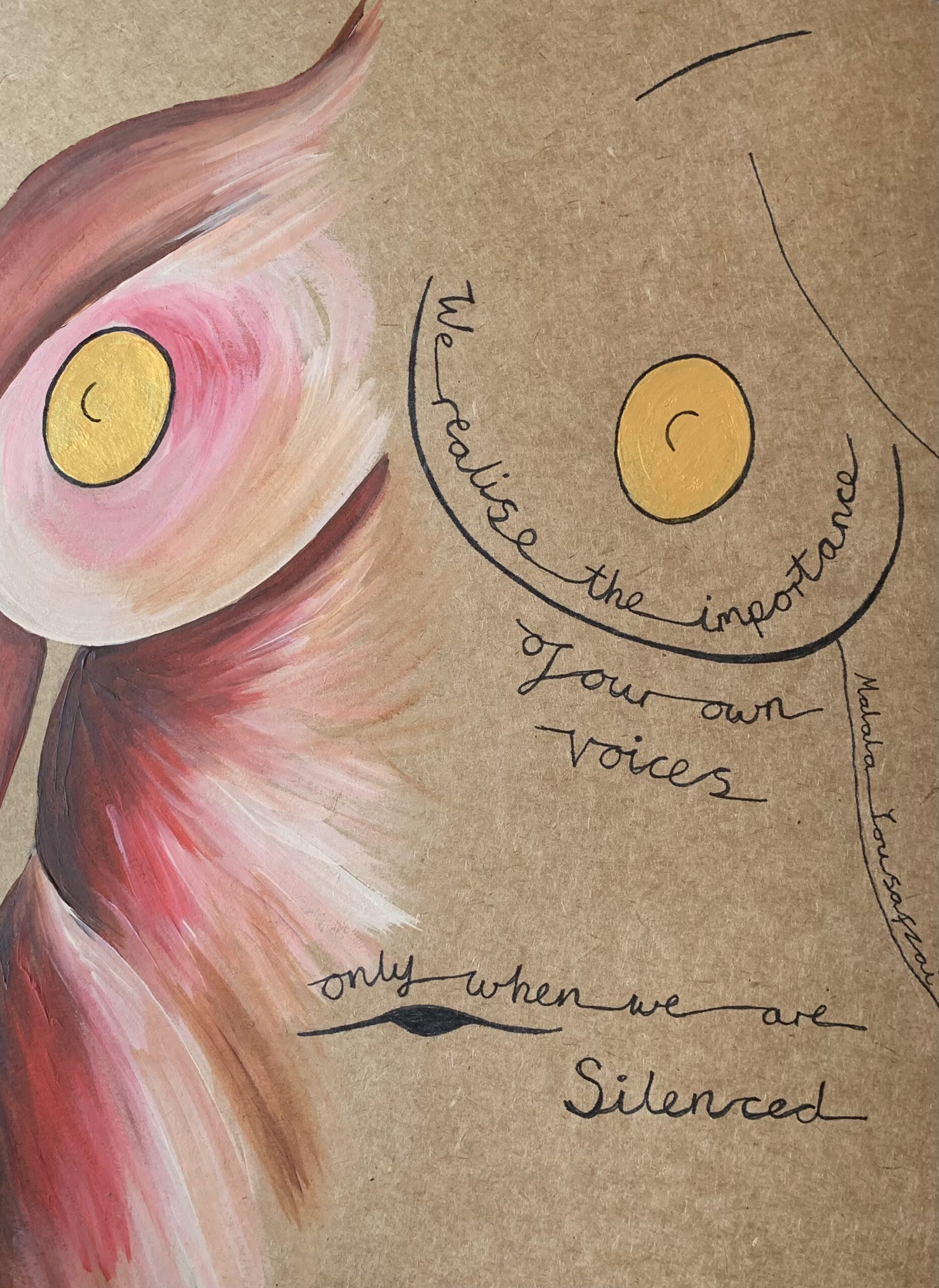

“We realise the importance of our own voices only when we are silenced.”

Malala Yousafzai

Malala Yousafzai (born on 12th July 1997), often referred to just as Malala, is a Pakistani activist for female education. She won the Nobel Peace Prize for her work in this area, becoming the youngest Nobel Prize laureate.

In many parts of the world, girls encounter brutal violence and cannot live freely. Today, over 130 million girls are denied education due to poverty, war and discrimination - 5 million of them in Pakistan.

Malala’s story:

Malala was born in the Swat Valley, where many of the Pashtun people still value boys more than girls. However, Malala’s father Ziauddin was a humanitarian and education activist, with different views. From the start, he encouraged her to reach her full potential. She attended his school in the Swat city of Mingora, where she learned, among other things, how different boys’ and girls’ lives were, and that men were always in charge. But she also learnt from her father that change was possible. He was a passionate advocate for women’s education and the right of everyone, regardless of background or gender, to go to school.

When Malala was ten years old, the Taliban came to the Swat Valley. They made bonfires of people's 'unsuitable' possessions and shut down cable TV. Children were not allowed to play or be vaccinated against polio. The Taliban pinned a letter to the gate of Ziauddin's school, warning him to stop the girls wearing the normal school uniform; they insisted the girls must wear burkas and cover their faces.

By 2008, the Taliban were using more violent methods to impose their rules, regularly blowing up schools – mostly girls’ schools. Malala, then eleven, was interviewed on several TV channels, speaking out for girls’ right to go to school. In a BBC interview, she said: “How dare the Taliban take away my right to education?”

Soon after, all girls' schools were forced to close and girls in the Swat Valley were forbidden to attend school. Excerpts from Malala's diary, describing life under the Taliban, were broadcast on BBC Radio under a pseudonym. Later, in a documentary, she said: “They cannot stop me... our challenge to the world around us is: save our school, save our Pakistan, save our Swat.”

Widespread protests caused the Taliban to partially relent and allow girls up to ten years old to attend school. Some older girls, such as Malala and her friends, continued to study in secret, hiding their schoolbooks under their shawls. In 2009, the Pakistani army moved in to oust the Taliban from the area, causing most people to evacuate. Malala’s family returned three months later, with the army claiming the Taliban were defeated - but soon school bombings began again. In her memoir, Malala describes her birthplace as "a heavenly place full of mountains, flowing waterfalls and clear lakes. The sign at the entrance to the valley reads ‘Welcome to Paradise’.” The Taliban were turning this paradise into a hell.

In January 2012, Malala travelled to Karachi with her family to speak at a school which was to be named in her honour. She said: “We want to be able to make our own decisions and be free to go to school or work. Nowhere in the Koran does it say that a woman should be dependent on a man or have to listen to a man.”

They were still in Karachi when Malala’s father saw on the internet that the Taliban had issued death threats against her. Proud of her but afraid for her safety, he urged her to stop speaking out against the Taliban, but she refused.

Malala was not allowed to walk to school anymore. Instead, she travelled by rickshaw to school, and came home on the back of the school ‘bus’—simply a truck with a canvas roof. One day, two men forced the truck to stop. One climbed into the back shouting, “Which one of you is Malala?” She was the only one without her face covered. The man fired three rapid shots—and the first hit Malala in the head. She was flown by helicopter to a military hospital, and then on to a hospital in the UK. She regained consciousness a week later, but the left side of her face had been paralysed. After an eight-hour operation, doctors managed to restore her facial nerves, and she began her recovery.

On 12 July 2013, her sixteenth birthday, Malala was invited to speak at the UN. The UN Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon, called the day ‘Malala Day’. He said: “I urge you to keep speaking out. Keep raising the pressure. Keep making a difference. And together let us follow the lead of this brave girl. Let us put education first. Let us make this world better for all.”

Malala replied: “Today is the day of every woman, boy and girl who has raised their voice for their rights. Let us wage a global struggle against illiteracy, poverty and terrorism. Let us pick up our books and pens, they are our most powerful weapons. Education is the only solution. Education first.”

The Taliban thought they could silence Malala by killing her, but instead, they gave her an even stronger voice, allowing HERstory and message to spread around the globe. She has set up the Malala Fund, which promotes girls’ rights to 12 years of free education in a safe environment. “I don’t want to be famous for being the girl who was shot by the Taliban. I want to be the girl who fights for education,” she explains. The Fund supports local activists in Syria, Nigeria, Pakistan and other countries where girls are affected by injustice and violence. “Extremists have shown what frightens them most – a girl with a book," says Malala. "With guns, you can kill terrorists, but with education, you can kill terrorism.”

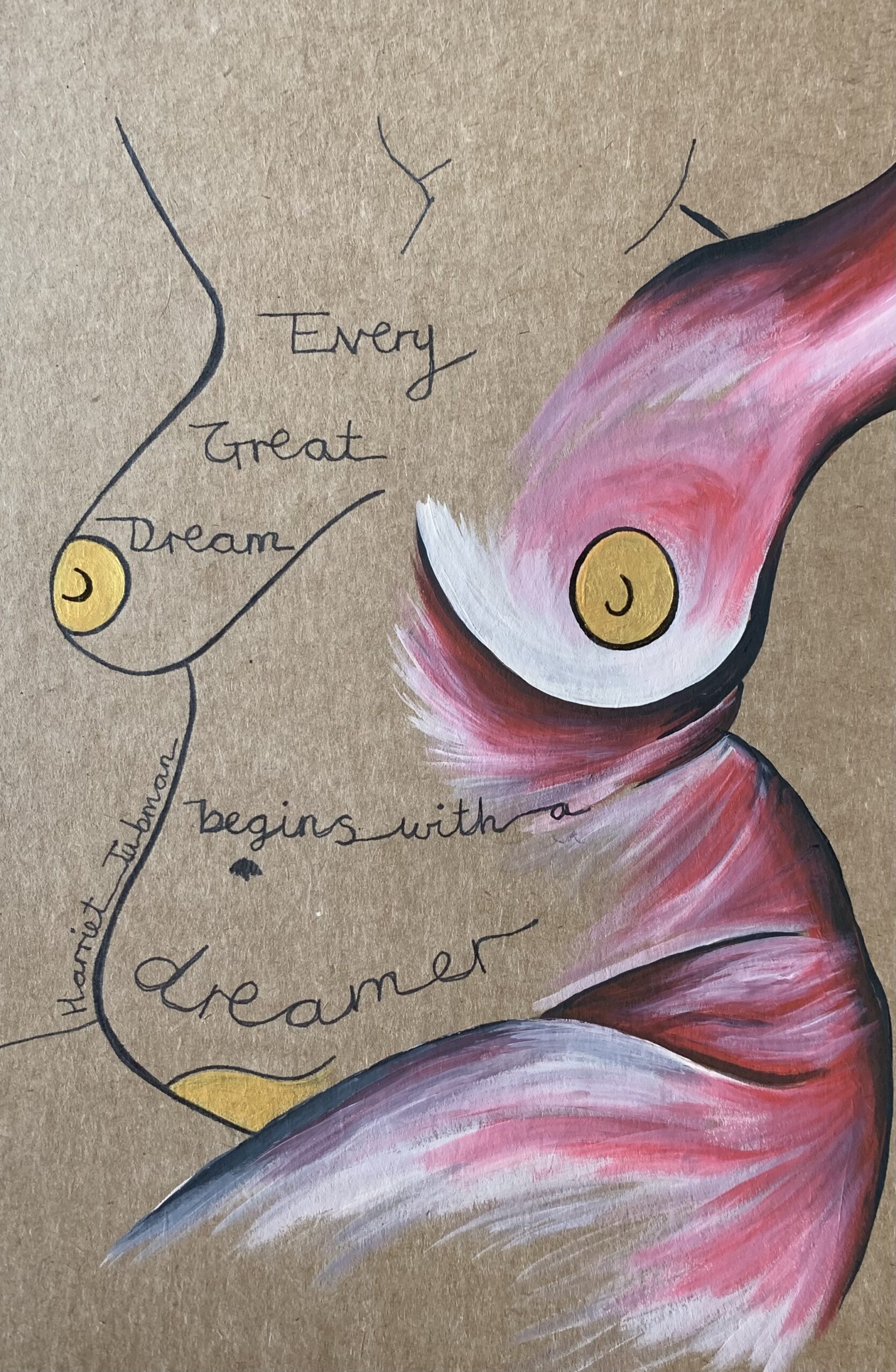

Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman was born Araminta Ross in Maryland, US, probably in early 1822. The daughter of her slaves and one of nine children, she was already being ‘lent’ to neighbours for domestic duties at age 5. Slavery meant that families like hers—she had eight siblings—were often separated, and all three of her sisters were sold to distant plantations, despite her parents’ efforts to resist this. Minty was only twelve when she refused to help restrain a runaway slave and was hit in the head with a two-pound weight. She suffered from seizures, severe headaches and narcolepsy for the rest of her life.

By 1840, her father was free under the stipulations of his manumission papers but had little choice but to remain with his family and continue working for his former owner. Minty married a free black man, farmer John Tubman, in 1944, although as a slave, her union wasn’t legally recognised. Around this time she took her mother’s first name too: Harriet.

Harriet finally escaped in 1849 and became a housekeeper in Philadelphia. Her husband refused to leave and quickly married again. Harriet was determined to help others escape, but the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 made her task more difficult; even states that had outlawed slavery had to assist in the return of runaway slaves. However, she spent the next decade helping family members—including her parents—and other groups escape slavery via the 'Undergound Railroad', directing or taking them to Canada to ensure they remained free. She rescued around 70 people from slavery and assisted dozens of others, and ‘never lost a passenger’. Her success put a $40,000 price on her head. During this period, she also met abolitionist John Brown and helped former slave Charles Nalle elude U.S. marshals.

“Every great dream begins with a dreamer.”

When the Civil War began, Harriet joined the military--probably the first African American woman to do so—and worked as a nurse. However, her rescue activities had given her extensive knowledge of the South’s geography and infrastructure, and she was soon working work as a spy and scout. She learned about Confederate deployments from slaves she talked to, repaying them with food, escape routes and job offers in the North. She also became the first woman to head a US military expedition, leading an armed raid that destroyed Confederate supplies and freed over 700 slaves.

After the war, Harriet raised funds to aid freed slaves and joined the quest for women’s suffrage. Having failed to secure payment for her war work, she worked with white writer Sarah Bradford on her autobiography, hoping it would provide an income. In 1869 she married Union soldier Nelson Davis, also born into slavery, and they adopted a daughter in 1874. After an extensive campaign for a military pension, she was finally awarded $8 per month in 1895 as Davis’s widow (he died in 1888) and $20 in 1899 for her service.

She finally opened the Harriet Tubman Home for the Aged in 1908 on land she had bought near her home in 1896 for this purpose. Sadly, by 1911, she was in poor health herself and became a resident there. She died in 1913 and was buried with military honours in New York.

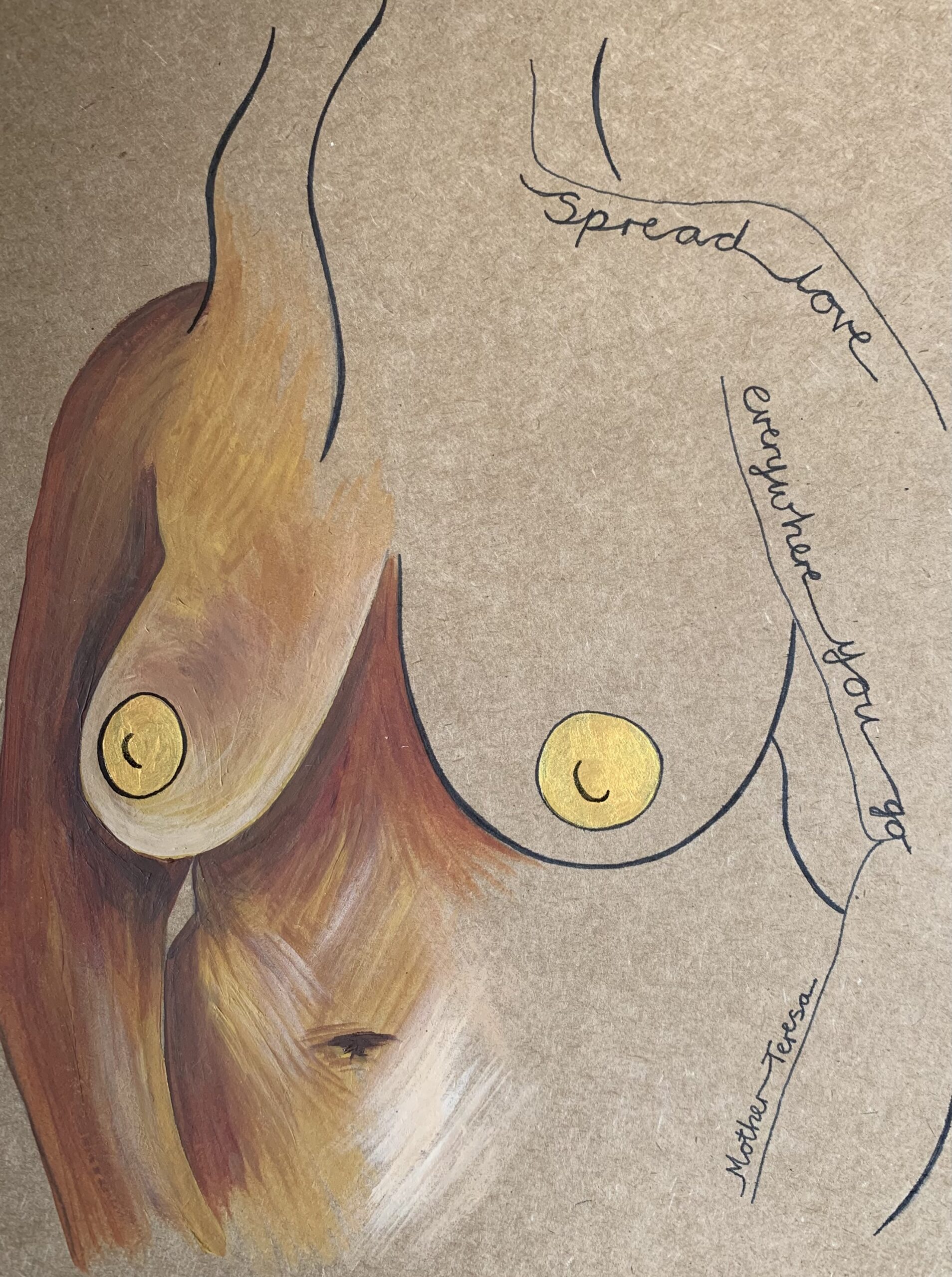

“Spread love everywhere you go.”

Mother Teresa

Spread love everywhere you go. Let no one ever come to you without leaving happier.”

Mother Mary Teresa Bojaxhiu (1910 – 1997), honoured in the Catholic Church as Saint Teresa of Calcutta, was a Roman Catholic nun and missionary of Albanian-Indian descent.

Mary (baptised as Agnes) was brought up in Skopje. She felt called to God at the age of twelve, and became determined to be a missionary. When she was eighteen, she travelled to Dublin to join the Sisters of Loreto. After a short period of training, she travelled to one of their missions in India and there, in 1931, she took her initial vows.

She spent the next 17 years teaching at St. Mary’s High School in Calcutta. During that time, she took her final vows (earning the traditional title of Mother used by the Sisters of Loreto, and became fluent in Bengali and Hindi.

She was dedicated to the education of these girls, who came from the very poorest families - but seeing the suffering and poverty all around her made her long to do more. However, it took another year for her to gain permission to be released from the order. In 1948, she finally left the school and devoted herself to hands-on work in Calcutta's slums instead. With no funds, she started an outdoor school for children, and as her work became known, she gained financial support and volunteers to help her in her work.

In 1950, Mother Teresa received permission from the Holy See to start The Missionaries of Charity, her own Order. The main purpose was to provide love and care for people with nobody else to provide it for them. The Order began with just a few members, primarily former pupils and colleagues from the school, but it soon grew. Over the next two decades, the Order set up a leper colony, an orphanage, medical clinics and a nursing home.

After being awarded the Decree of Praise by Pope Paul VI, Mother Teresa began to expand the Order's work overseas, establishing charity houses around the world to help disaster victims, alcoholics, homeless people, and AIDS sufferers.

When she died in 1997, the order had 4000 members (including Brothers and Priests), and ran 610 foundations in 123 countries. The Order is still active today, with thousands of volunteers, and cooperates with many other charitable organisations worldwide.

Mother Teresa received many awards for her work. They include the Jewel of India (the highest civilian honour in India), the Soviet Union's Gold Medal of the Soviet Peace Committee, the Pope John XXIII Peace Prize (1971), and the Nehru Prize for her promotion of international peace and understanding (1972). In 1979, she was awarded both the Balzan Prize and the Nobel Peace Prize - the latter in recognition of her work "in bringing help to suffering humanity."

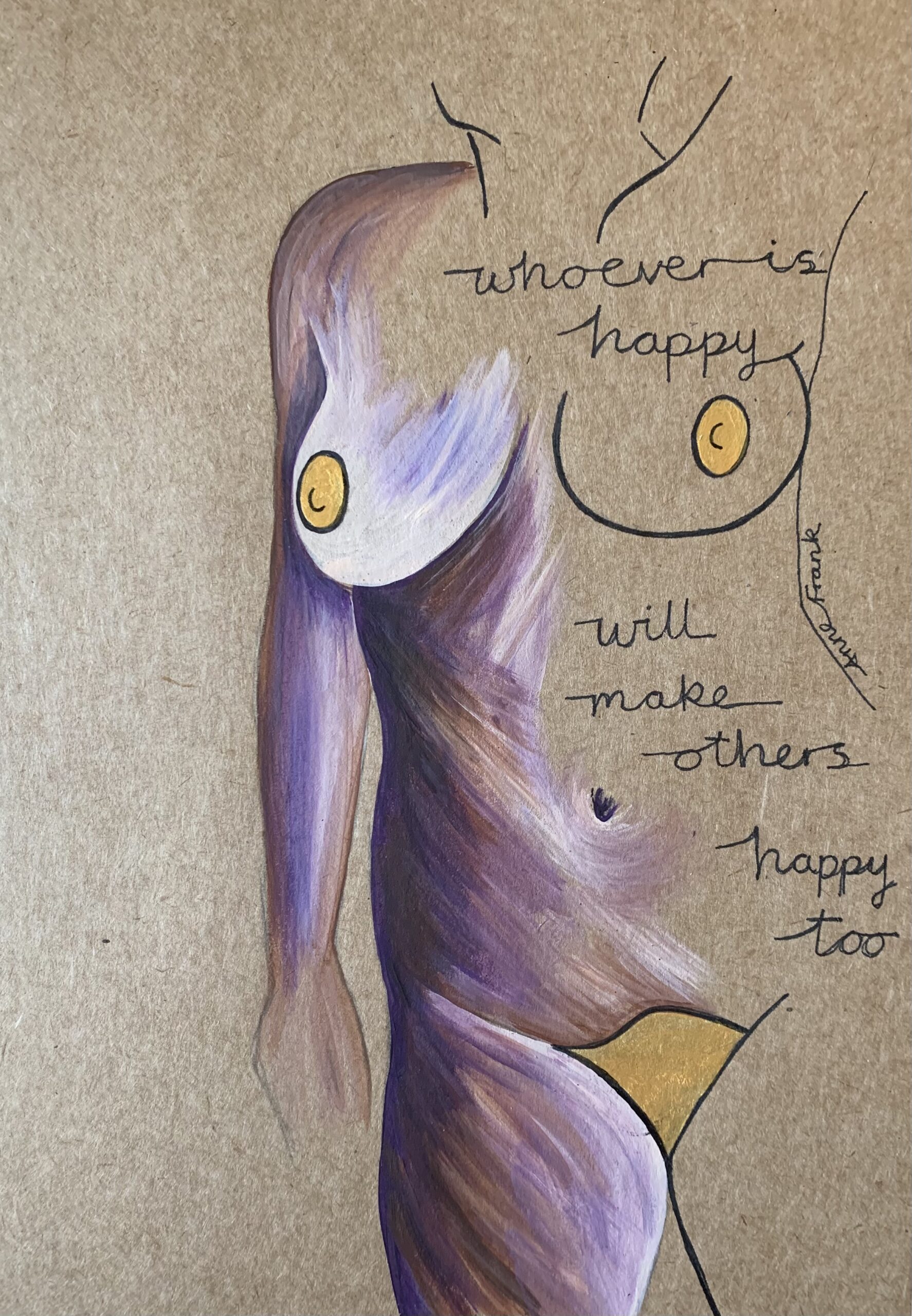

Anne Frank

Annelies Frank was born in 1929 in Frankfurt, Germany. However, her parents, Otto and Edith, became concerned about Hitler's rise to power, the dire economic situation, and growing antisemitism. By 1934, they had moved their family to Amsterdam. Anne and her sister Margot settled into a new home and school, and all was well for a time.

By 1940, though, World War II was underway, and the Nazis had invaded the Netherlands. Under their regime, Jewish people couldn’t visit non-Jewish businesses or attend non-Jewish schools. Soon, they were required to wear a Star of David to mark them out. In 1942, Jewish people began being called to report for ‘work’ at Camp Westerbork near the German border. Many were unaware that this was just a staging post for Nazi transportation to Auschwitz-Birkenau and Sobibor, camps where hundreds of thousands of Jews were killed, but others had heard rumours. When Margot received her instructions to report to a German labour camp in July, the Franks decided they should go into hiding immediately.

Anne had received a diary for her 13th birthday just a few weeks before, and in this, she documented this tense and terrifying time for the family. On 6th July, they went into hiding in a loft annexe behind the office they owned at Prinsengracht 263, with helpers concealing the entrance. They were soon joined by four Dutch Jews.

The group hid in the Secret Annexe for two years, undiscovered despite a couple of close calls, aided by friends who brought them food and other essentials.

“Whoever is happy will make others happy too.”

Unfortunately, on 4th August 1944, the family’s hiding place was discovered by the Gestapo (German Secret State Police). They arrested the Franks, their four companions, and two of the friends who had assisted them. They were all sent to Camp Westerbork shortly after, and transported to Auschwitz in Poland a month later. There, men and women were separated, and due to their youth, Anne and her sister were chosen for manual labour. In October, Anne and Margot were transferred to the infamous Bergen-Belsen camp, where conditions were horrific, Sadly, they both contracted typhus and died in March of 1945, just a few weeks before the British liberated the camp on 15th April.

Their mother had already died in Auschwitz in January, shortly before its liberation by the Soviet army. However, their father survived. When he returned to the Netherlands, he discovered that his friend Miep Gies had found Anne’s diary before the Nazis raided the annexe and kept it safe. After reading his daughter’s diary, and of the ambitions she expressed in it to become a writer, he decided her diary should be published.

Anne Frank’s diary was published in June 1947 and became a huge bestseller, later translated into over 70 languages. In 1960, the secret annexe where the family hid was turned into a museum, Anne Frank House.

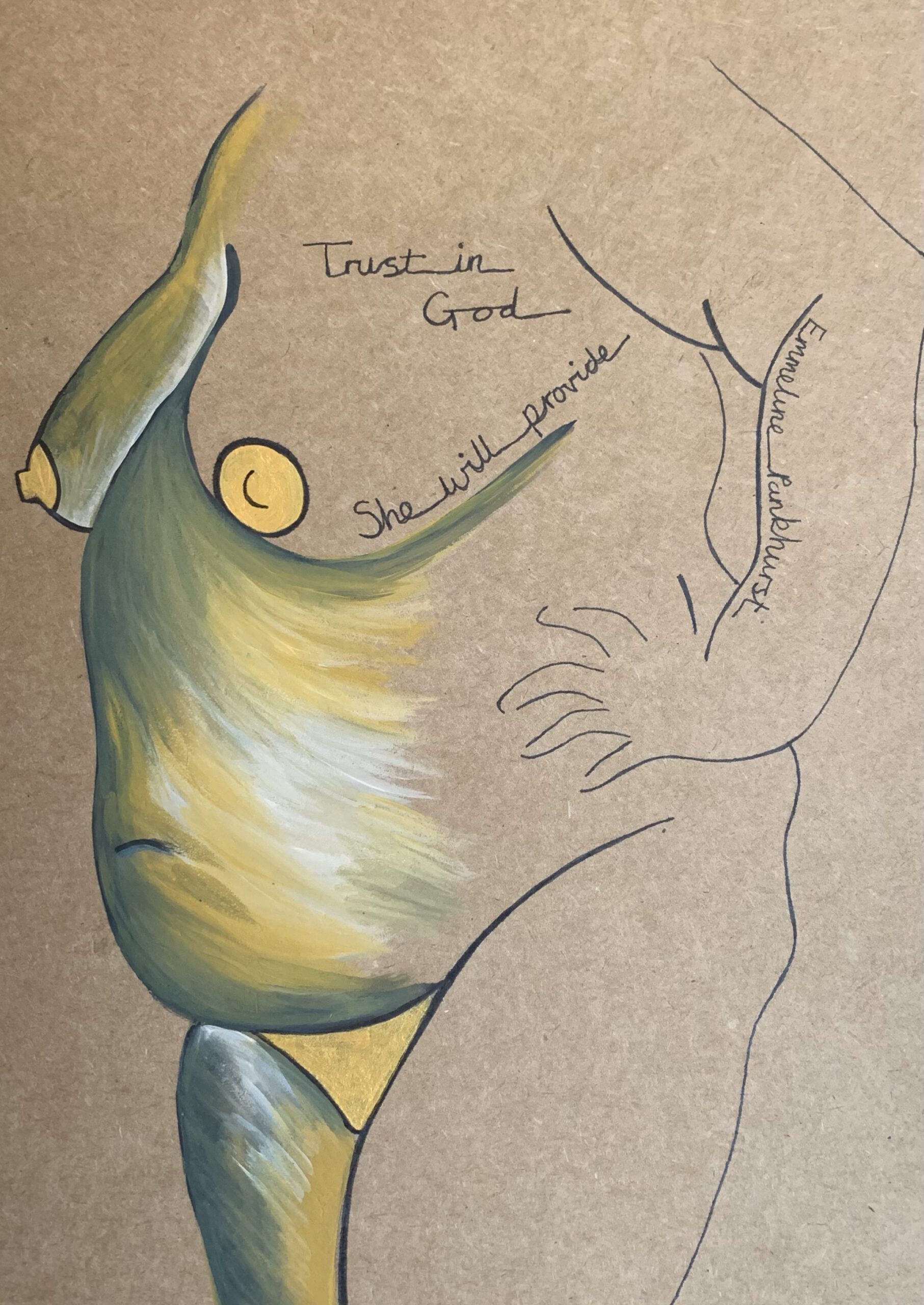

"Trust in God – She will provide.”

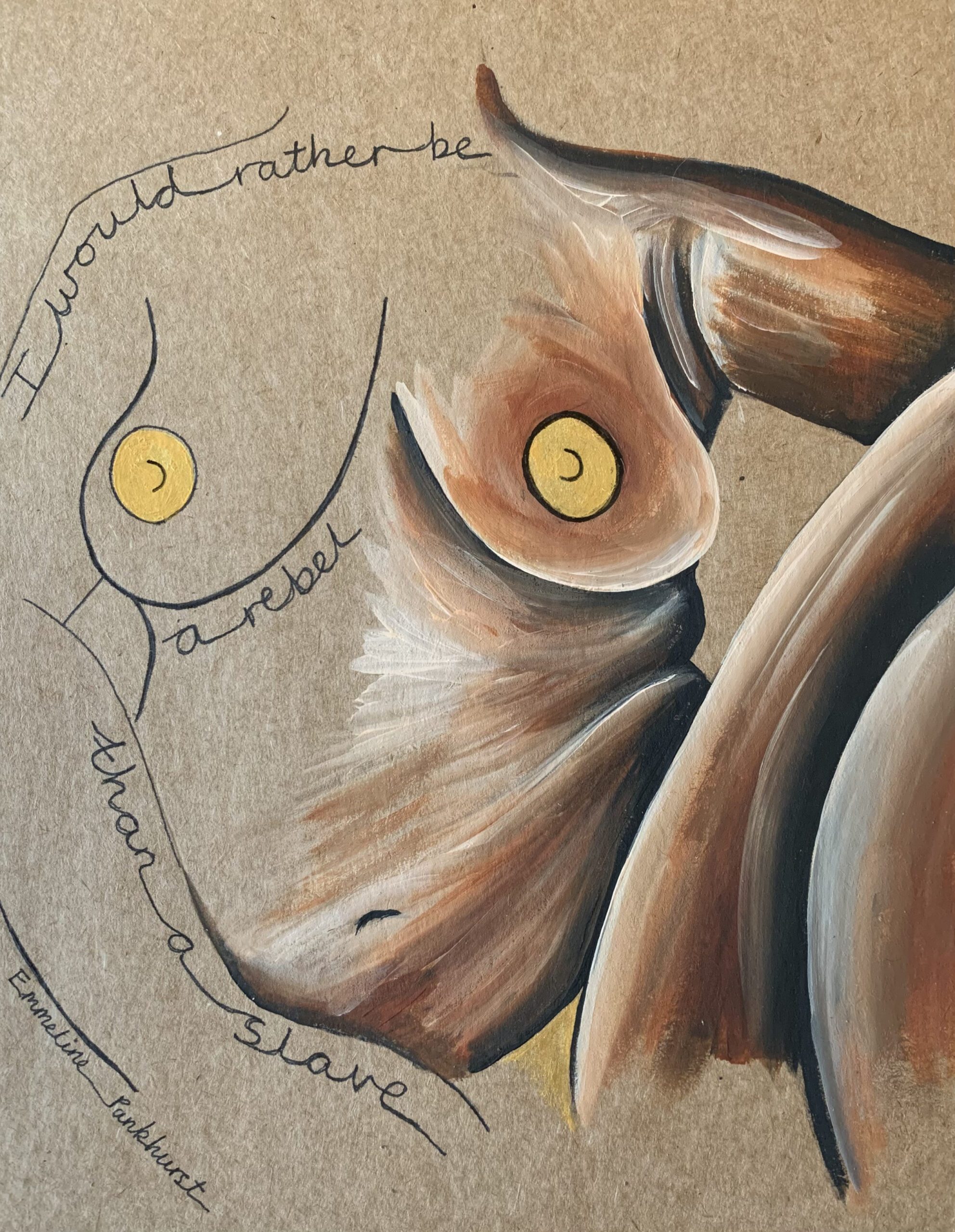

Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst (1858 – 1928) was a British political activist, famous for leading the UK's suffragette movement.

Emmeline Goulden was born into a Manchester family with radical political ideas on both sides. She was only 14 when she became determined to campaign for the right of women to vote, after attending a political talk with her mother. That cause became the guiding principle of her life. Despite her parents' support of women's voting rights, though, they didn't believe that women could perform as well as men academically or in the workplace.

In 1879, she married lawyer Richard Pankhurst. Richard supported women's suffrage and had written the Married Women's Property Acts of 1870 and 1882, which allowed women to keep earnings or property acquired before and after marriage.

“I would rather be a rebel than a slave.”

They had five children over the next decade, one of whom died young, but Pankhurst kept campaigning, employing staff to help with childcare.

In 1889, Emmeline co-founded the Women's Franchise League, which campaigned for the voting rights of both married and unmarried women - at odds with other suffragette movements that considered married women did not need the vote, as their husbands 'voted for them.'

Voting rights for women were not Emmeline's only concern. She worked as a Poor Law Guardian and became very concerned for the poor and oppressed in society. She believed that not only did women have the right to vote, but that society would be the better for it. She also supported her husband in his unsuccessful attempts to be elected as an MP, and tried unsuccessfully to join the Independent Labour Party, attracted by the range of issues they wanted to tackle. The local branch rejected her application on the grounds of her sex, but she was later granted membership on a national level.

Her campaigning began to involve her in legal battles, with her husband acting as counsel. His death in 1898, while she was abroad, was a great shock to her - and left her in considerable debt. She moved her family to a smaller home and took a paid position as Registrar of Births and Deaths in Chorlton.

In October 1903, she helped found the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU); her three daughters were members too. They had a more militant outlook than the WFL and their motto was ‘deeds not words’, but they tried to campaign peacefully at first. However, they became desperate in the face of continued opposition; disruptive demonstrations, hunger strikes, and sometimes arson and vandalism, became integral to their campaigning. Pankhurst was arrested numerous times and force-fed during hunger strikes. Another member, Emily Davison was killed when she threw herself under the king's horse at the 1913 Derby to protest at the government's continued refusal to grant women the vote.

It wasn't until 1918 that the Representation of the People Act gave voting rights to women over 30, and this age limit was lowered to 21 in 1928. Sadly, Pankhurst had died three weeks beforehand, unable to witness the granting of a right she had campaigned so hard for.

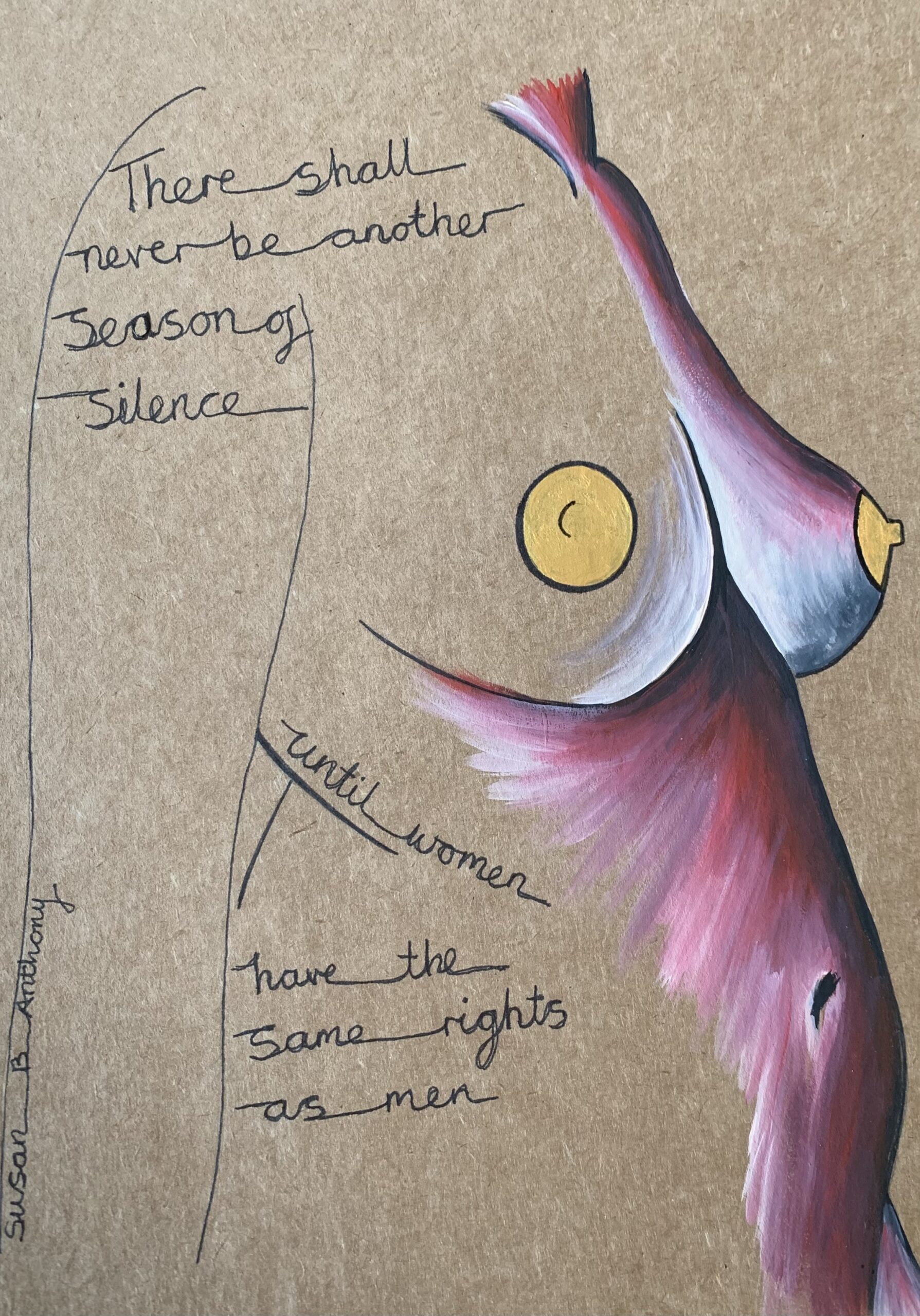

Susan B Anthony

Susan B. Anthony was a social reformer who played a pivotal role in the women's suffrage movement.

Born into a Quaker family in Massachusetts in 1820, Anthony was raised to believe in social equality from a young age, and that everyone was equal under God. Her father, a farmer and cotton mill owner, did all he could to avoid buying cotton grown on farms using slave labour. Unsurprisingly, some of her siblings became activists too. Equality meant education for girls as well as boys, and she both learned and taught in the home school before going to the Friends’ Seminary near Philadelphia in in 1837.

In 1845, her family moved to Rochester, New York and became actively involved in the anti-slavery movement, holding meetings attended by famous abolitionists such as Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison. Meanwhile, Anthony began teaching and joined the teacher’s union. She soon discovered that male teachers were paid four times as much as female teachers, and this injustice sparked a lifelong dedication to gender equality.

In 1851, she became a dedicated suffragist after meeting and befriending Elizabeth Cady Stanton—famous for organising the first women's rights convention at Seneca Falls. The two women campaigned together for women’s rights around the country., Anthony spoke passionately on women’s rights and suffrage, ignoring those who said women should not make public speeches. She also spoke at abolitionist gatherings, and in 1861, accused Abraham Lincoln of being too moderate, saying there could be “no compromise with slaveholders.”

“There shall never be another season of silence until women have the same rights as men on this green earth”.”

Anthony and Stanton co-founded the American Equal Rights Association and in 1868 they became editors of its newspaper, The Revolution. They also formed the National Woman Suffrage Association, campaigning for a constitutional amendment giving women the right to vote. In 1872, Anthony was arrested for voting and had to pay a fine of $100 for her ‘crime’, bringing wider attention and support to her cause. However, Anthony died in 1906, 14 years before women were given the right to vote with the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920.

“When your heart is right, your mind and body will follow.”

Coretta Scott King

Coretta Scott was born in Alabama in 1927. Musical like her mother, she soon led choirs in school and church. She attended Antioch College in Ohio, where she joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the Race Relations and Civil Liberties Committees. After graduating with a BA in Music, she enrolled at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston in 1951 and met Martin Luther King, Jr, a postgrad theology student at Boston University. They married in 1953, and after graduating in 1954 they moved to Alabama where Martin became a Baptist pastor. Their involvement in the historic Montgomery Bus Boycott made Martin influential; soon, his Dexter Avenue Baptist Church became a centre for the Civil Rights Movement in Alabama, and eventually the country.

Alongside her husband, Coretta became a target for white supremacist groups and received death threats. However, she campaigned by his side and travelled the world with him when she could; at other times, she remained at home caring for their four children. Despite her criticism of the Movement's exclusion of women, Coretta performed at freedom concerts that combined poetry, songs, and lectures about the Movement.. She also went attended the 17-nation Disarmament Conference in Gneva as a Women’s Strike for Peace delegate; worked as a liaison to peace and justice organisations and as a public mediator; and was involved in efforts to pass the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Martin did not always approve of his wife’s attempts to speak in public and provide leadership, and this may be what saved her life, as he told her not to accompany him on the day of his assassination. On 4th April 1968, Martin was shot and killed in Tennessee.

Four days later, Coretta led his planned march in Memphis to support striking sanitation workers. This determination to continue supporting Martin's causes and preaching his message of non-violence continued through her life.

Coretta founded the Martin Luther King, Jr., Center for Nonviolent Social Change (commonly known as the King Center) in Atlanta, in 1968, which she led until her son took over on her retirement in 1995. She established an annual Coretta Scott King Award to honour an African American author of an outstanding text for children in 1969 and added a similar ward for an African American illustrator in 1979. She also campaigned for a national day to honour her husband, which was passed into law in 1983.

Coretta continued speaking on, and advocating for, the civil rights of all groups—women, LGBT, people of colour—and for peace, right up until her death. She died in January 2006, and the attendance of several presidents and heads of state at her funeral served as a reminder of just how vital she was to the Civil Rights Movement. The Coretta Scott King Center at Antioch College, which focuses on human rights and social justice, was opened in 2007 in her honour.