Changing History to HERstory: Icons of the Visual Arts

This in-person exhibition became an online sensation due to Covid restrictions. Thanks to its immediate popularity, it quickly became a book, published by Girl God Books.

We live in a world predominantly shaped and dictated by men, so for International Women's Day 2021, Kat Shaw decided she would pay tribute not to history, but to HERstory. Her exhibition recognised and celebrated the wonderful women who have shaped the way the world, even if this was unnoticed at the time. Kat, and many other women, are noticing NOW - and giving these women the respect they deserve.

On this page, we look at the icons of the visual arts - artists of all kinds, and fashion designers - who inspired Kat. To discover all the talented women who acted as muses for Kat's exhibition - writers, scientists & explorers, protesters, politicians, and stars of sport, screen and music - visit the exhibition's homepage.

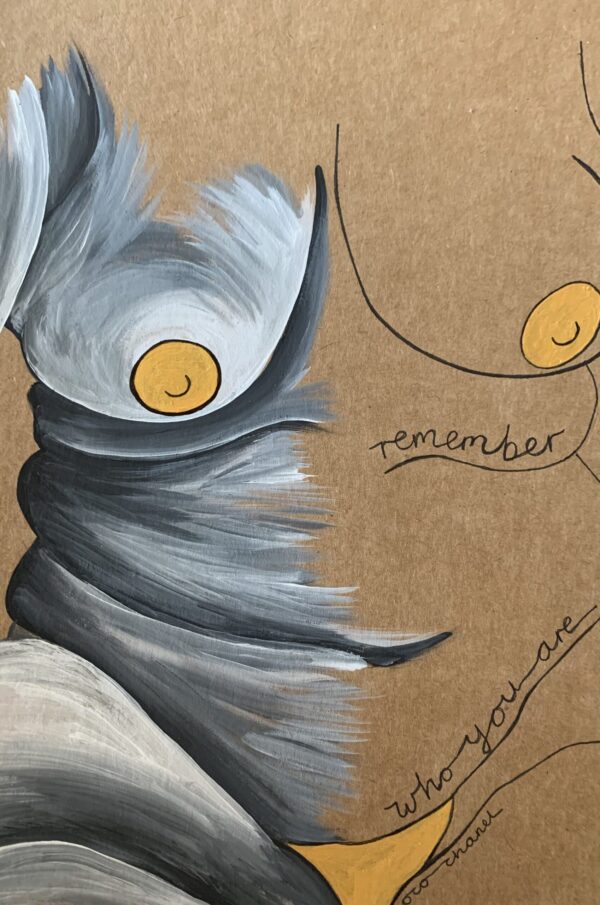

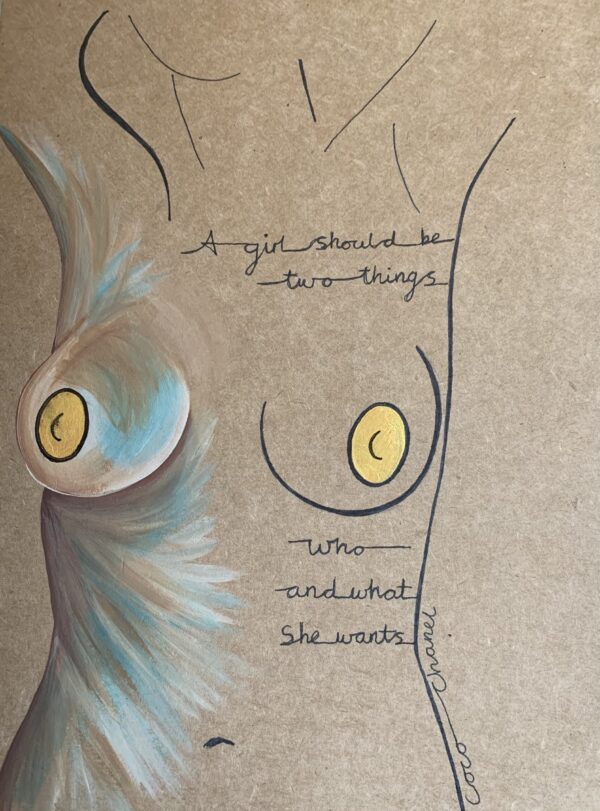

Coco Chanel

“Always have in mind your true worth – self-awareness leads to self-confidence and self-confidence leads to self-love. And all are crucial.

Remember who you are, where you come from and where you are going.”

Gabrielle Bonheur “Coco” Chanel (1883 – 1971) was a French fashion designer and businesswoman. The founder and namesake of the Chanel brand, she was credited in the post-World War I era with popularising a sporty, casual chic as the feminine standard of style, replacing the 'corseted silhouette' that was dominant beforehand. Coco literally liberated women – by stripping off the constraints of corsets, she unapologetically gave them back their right to breathe and introduced a new, bold, modern style of leveraging elegance which women embraced gladly.

The legendary fashion designer and true icon of style was also a remarkably intelligent and audacious woman. Apart from her creative ingenuity and a sharp eye for sophisticated aesthetics, she was an incredibly empowering woman who continues to empower women of all generations.

“Remember who you are.”

"A girl should be two things: Who and what she wants.”

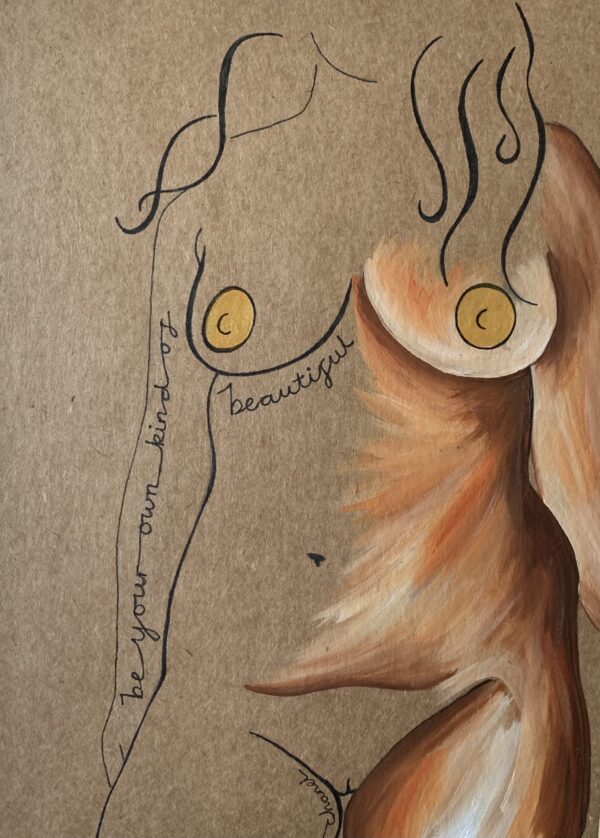

"Be your own kind of beautiful.”

“I am my own muse.”

Frida Kahlo

“I am my own muse. I am the subject I know best. The subject I want to better."

Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón (1907-1954) was a Mexican painter known for her many portraits, self-portraits, and works inspired by the nature and artefacts of Mexico. Her thought-provoking work, based in magical realism, was known around the world, and her 1938 self-portrait, The Frame, was the first work by a 20th-century Mexican artist to be featured in the Louvre.

Kahlo suffered from polio as a child and nearly died in a bus accident as a teenager, which left her with health problems for the rest of her life. It was while recovering from her multiple serious fractures, encased in a body cast, that she began to focus on painting while recovering in a body cast. In her lifetime, she had 30 operations and also suffered miscarriages as a result of damage to her pelvis.

“I used to think I was the strangest person in the world.”

Frida's work is recognisable by its bold, vibrant colours. It is praised for depicting Mexican and Indigenous culture and acknowledging the female experience and form. In her body of work, which consists of around 200 paintings, sketches and drawings, she depicts her physical and emotional pain, including her difficult relationship with her husband, artist Diego Rivera- whom she married twice. 55 of her 143 paintings are self-portraits. She explained: “I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best."

Although she was occasionally commissioned to paint portraits, Kahlo sold few paintings in her lifetime. There was just one solo exhibition of her work in Mexico in 1953, just a year before she died, aged 47. However, her work has gained popularity and value in the decades since her death. In May 2006, one of her self-portraits, Roots, sold for $5.62 million at a Sotheby's auction in New York. This was a new record: the most expensive Latin American artwork ever purchased at auction.

She was unapologetic about her identity as a woman, a feminist, and a bisexual, and about her choice of lovers, including American-born French entertainer Josephine Baker. Despite her looks being referred to as 'masculine', she refused to get rid of her faint moustache or monobrow, and even exaggerated them in her self-portraits. She dressed as she wanted, in bright, bold dresses, and often wore flowers and ribbons. Her art pushed boundaries too, touching on issues seen as highly taboo at the time, such as abortion, miscarriage, birth and breastfeeding.

Frida Kahlo is recognised today not just for the talent displayed in her work, but also her determination in the face of hardship and the gender bias of society. Her defiance of social conventions continues to be an inspiration for many.

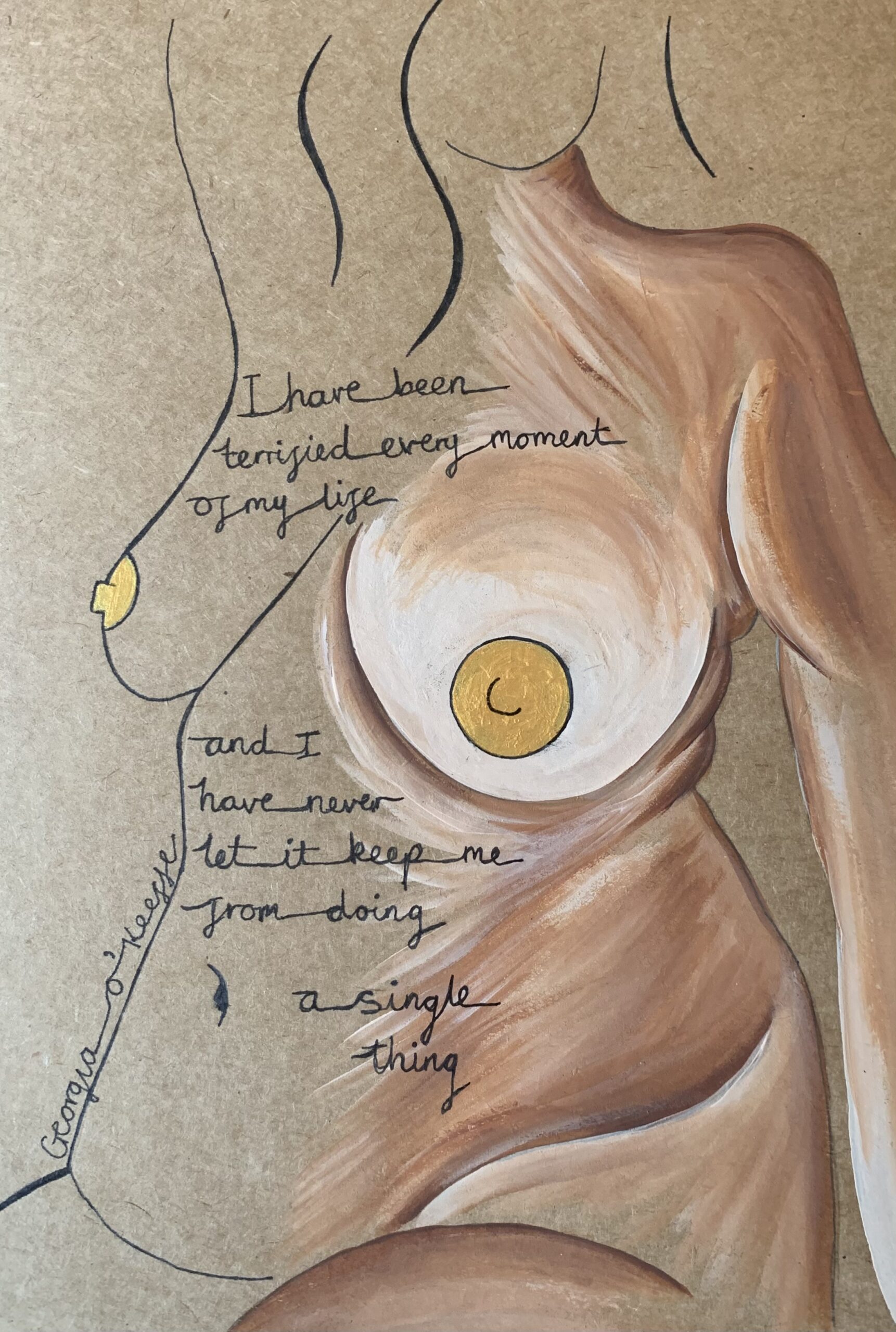

Georgia O'Keeffe

Georgia Totto O'Keeffe (1887 – 1986), an American artist, was integral to both American modernism and feminism. She is known primarily for her paintings of enlarged natural objects such as flowers.

O'Keeffe was raised on a Wisconsin dairy farm. Her artistic talent was encouraged at home and school; she and her sisters had lessons from local watercolourist Sara Mann. After graduating high school, she attended the Art Institute of Chicago from 1905-6, then, after a bout of typhoid fever, she attended the Art Students League in New York City in 1907-8. Here, the course was dominated by realism. She won the William Merritt Chase still-life prize in 1908 for her painting, Untitled (Dead Rabbit with Copper Pot), winning a scholarship to the League's summer school in New York.

At this point, circumstances conspired to stop o'Keeffe painting for the next four years. She learned her father had gone bankrupt and her mother was ill with TB, so there was no way to finance more study. She didn't want to work in the mimetic tradition in which she'd primarily been taught. She took a job as a commercial artist in Chicago until 1910, then moved to her family's new home in Virginia, first to recuperate from measles and then to teach art. It was there, at a summer course for art teachers in 1912, that she came across the concept of abstraction and Arthur Dow's Japanese-influenced approach: the idea that art could be about expressing the artist's feelings and thoughts rather than a literal rendering of what they could see,

This inspired her to start creating again, and in 1915, while still teaching, she produced a set of abstract charcoal drawings that she sent to a former classmate, Anita Pollitzer, in New York. Pollitzer showed them to Alfred Stieglitz, a well-known photographer, who exhibited them in his famous 291 gallery.

“I have been absolutely terrified every moment of my life – and I have never let it keep me from doing a single thing.”

Watercolours followed, and in 2018 she moved to New York to take up Steiglitz's offer of support: finance, accommodation, and a place to paint. Their professional relationship soom became a personal one, despite the fact he was married. His divorce was a lengthy process, and he didn't marry O'Keeffe until 1924. His work included hundreds of nude photographs of her, and this, combined with her bold work and the sexual interpretations often attributed to it - expecially by Steiglitz himself - added to her reputation as an edgy, sexually-liberated artist and woman.

However, as a member of the radical feminist National Woman’s Party, O'Keeffe rejected the idea that women have certain inherent character traits, and the gendererd interperetations of her work. She disliked Steiglitz's sexualized public portrayal of her, and after the Anderson Galleries exhibition of 1923, she went out of her way to change her public image. She promoted herself as a serious, professional artist - writing HERstory instead of his.

Stieglitz continued to promote his wife's work, especially the close studies of flowers that she started to paint in the mid-1920s. She had numerous one-woman gallery exhibitions, and her first retrospective, 'Paintings by Georgia O’Keeffe', opened at the Brooklyn Museum in 1927. Despite working in a world dominated by men, who were often critical of female artists, this success continued throughout her career. She once said, “The men liked to put me down as the best woman painter. I think I’m one of the

best painters.”

From 1929 onwards, she spent part of the year in the Southwest, and three years after Stieglitz's death in 1946, O’Keeffe moved to New Mexico, drawn by its landscapes and vibrancy. She spent the next 40 years there, apart from travels abroad. She was a canny businesswoman and sometimes bought back her works at auction, helping to stimulate the highly lucrative market for her art.

Although macular degeneration made oil painting difficult from the 1970s onwards, she continued to work in pencil, watercolor, and clay, sometimes with the help of an assistant. She was awarded the Medal of Freedom in 1977 and the National Medal of Arts in 1985.

She moved to Santa Fe and stopped working when her health worsened in 1984, and died there two years later, at the age of ninety-eight. It was here that the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum - the first museum in the United States dedicated to a single female artist - opened in 1997, providing a home for over 1000 of her works.

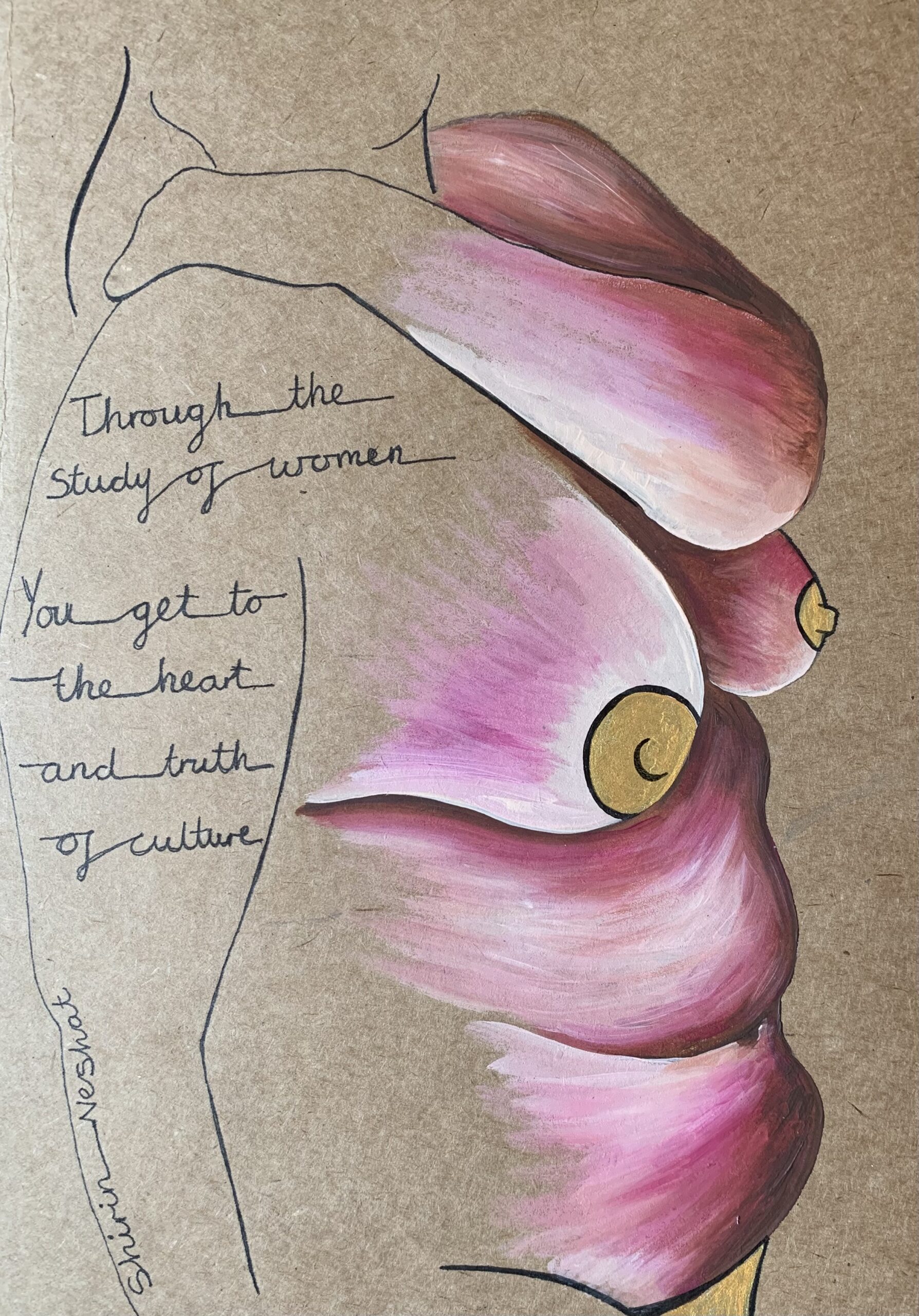

Shirin Neshat

“I find that through the study of women, you get to the heart – the truth – of the culture.”

Shirin Neshat is an Iranian filmmaker, photographer and videographer. She was born in 1957 in Qazin, Iran, to parents who supported Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, the shah of Iran, and his reforms that helped to emancipate and empower women. This meant that Neshat and her sisters attended boarding school. In 1975, she went to the University of California at Berkeley to study art. She attained her BA four years later and an MFA in 1982.

In her absence, her country of birth had undergone dramatic change. In 1979, revolutionaries overthrew the Shah and established an Islamic republic under Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, a Shiʿi religious leader. The Iranian hostage crisis and Iraqi invasion followed, so returning to Iran was virtually impossible.

Neshat moved to New York in 1983 and began working at Storefront for Art and Architecture, an exhibition and performance space. Shortly after, she married the founder, Korean artist and activist Kyong Park. In her ten years working there and raising their son, she created very little art and destroyed much of it, dissatisfied with the results.

She returned to Iran to visit in the early 90s, after Khomeini's death, and found the changes there shocking. This, coupled with exposure to the diverse creators and art forms at Storefront, proved inspiring.

“Through the study of get to the heart and truth of culture.”

In 1993, Unveiling, a sequence of stills, emerged from her re-ignited creativity, and she went on to produce the series Women of Allah from 1993-97. The black and white photographs focused on how gender, identity and society interact, and included pictures of Neshat in a chador, a garment that conceals everything except the hands. Neshat wrote in Farsi on her face, quoting a controversial feminist Iranian poet.

Since then, her bold work has continued to focus on contradictions and intersections between Eastern and Western culture and between the experiences of men and women - for instance, how veiling could symbolise both liberation and oppression for women.

Working across film, photography and video, she has achieved international fame and acclaim with works such as Rapture (1999). Turbulent (1998), a split-screened video, won the First International Prize at the Venice Biennale, and she won the Silver Lion at the 2009 Venice Film Festival for her directorial debut Women Without Men.

Neshat's work has been featured in exhibitions at MoMA and the Tate Modern, and the Huffington Post named her Artist of the Decade in 2010. She has staged an opera, worked on a multimedia production, and been awarded prizes, an honorary professorship, and artist residencies. Ultimately, though, her art - in whatever form - is inextricable from the causes that drive and inspire her.

She took part in a three-day hunger strike at the UN Headquarters in New York, protesting against the corrupt 2009 Iranian presidential election and in 2022, she protested after the suspicious death of Mahsa Amin. Amin died in hospital while under arrest for allegedly not wearing her hijab correctly.

In recent years, her work has also reflected her experiences of issues in other countries, including Morocco, Egypt, Turkey, and the US under the leadership of Donald Trump.

“I found myself, I made myself, and I said what I had to say.”

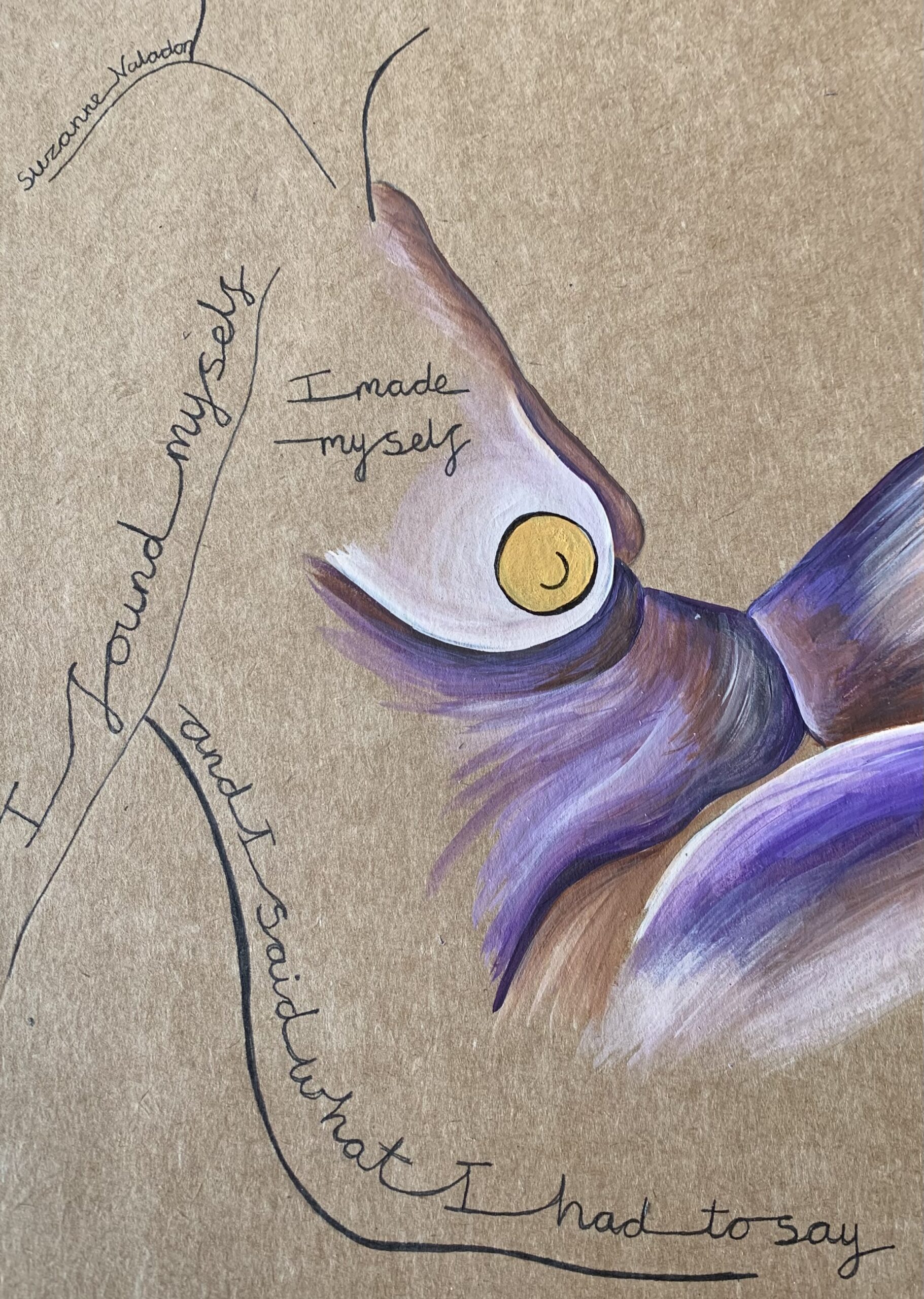

Suzanne Valadon

“I had great masters. I took the best of them and of their teachings and their examples. I found myself, I made myself and I said what I had to say.”

Suzanne Valadon, born Marie-Clémentine Valadon in 1865, lived in the bohemian, village-like Montmartre area of Paris from the age 5. Lively and headstrong, she spent her younger years drawing on any surface available and rebelling against her restrictive convent education. However, art as a profession only became appealing after an injury ended her career as a circus performer.

Unable to afford art lessons, she turned to modelling, which allowed her to socialise with and learn from artists while earning money. It was while modelling for Toulouse-Lautrec that she changed her name to Suzanne, after he likened her to a biblical story in which a young girl, Susan, spends her time amongst older men. She also modelled for Renoir (who may have been the father of her child, Maurice, born when she was 18) and others. Edgar Degas, whom she met in 1889, became her first buyer and biggest supporter.

Valadon was as well-known for her lovers, bohemian lifestyle and rebellious attitude as she was for her daring art; it didn’t receive widespread attention until she was in her late 20s. She became the first woman painter to have work admitted at the Salon of the National Society of Fine Arts in 1894. She exhibited 12 etchings of women in various stages of their toilette in 1895, when she also began to regularly show at the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune in Paris.

However, her art career was pushed aside for over a decade; she moved out of Paris with her husband, Paul Mousis, and spent time with her son Maurice. During a troubled boyhood, he had been primarily cared for by Valadon's mother for years; her 'treatment' of his mood swings with alcohol had turned him into an alcoholic adult. Valadon attempted to channel Maurice's energy into painting, and he eventually achieved great success. Although Degas continued to submit Valadon's work to exhibitions, she didn’t give her art career full attention again until she was 45.

After leaving her husband for artist André Utter—a friend of Maurice'ss, 21 years her junior—Valadon began to paint prolifically. Her painting, Summer, was accepted into the up-and-coming Salon d'Automne in 1909, and she held her first solo show in 1911. She continued to paint people as they were, ignoring contemporary art trends and historical traditions to convey realistic rather than idealised scenes. She used bright colours and bold outlines to portray both women and men in modern clothes or nude, pubic hair and all—and painted herself in the nude until well into her 60s.

In the last decade of her career, Valadon exhibited worldwide, with shows in New York, Prague, Chicago and Berlin. She died in 1938 at the age of 72, after suffering a stroke.

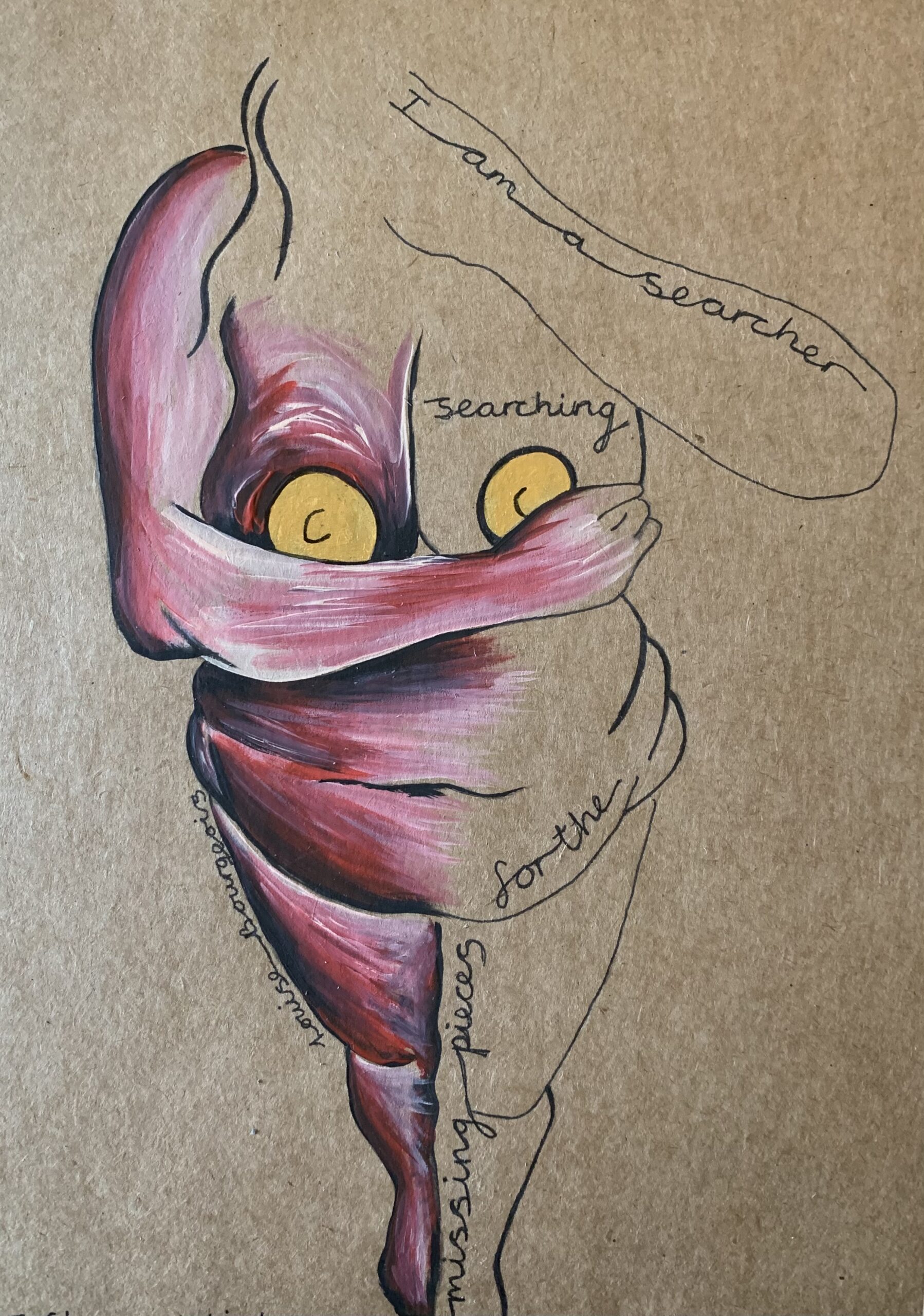

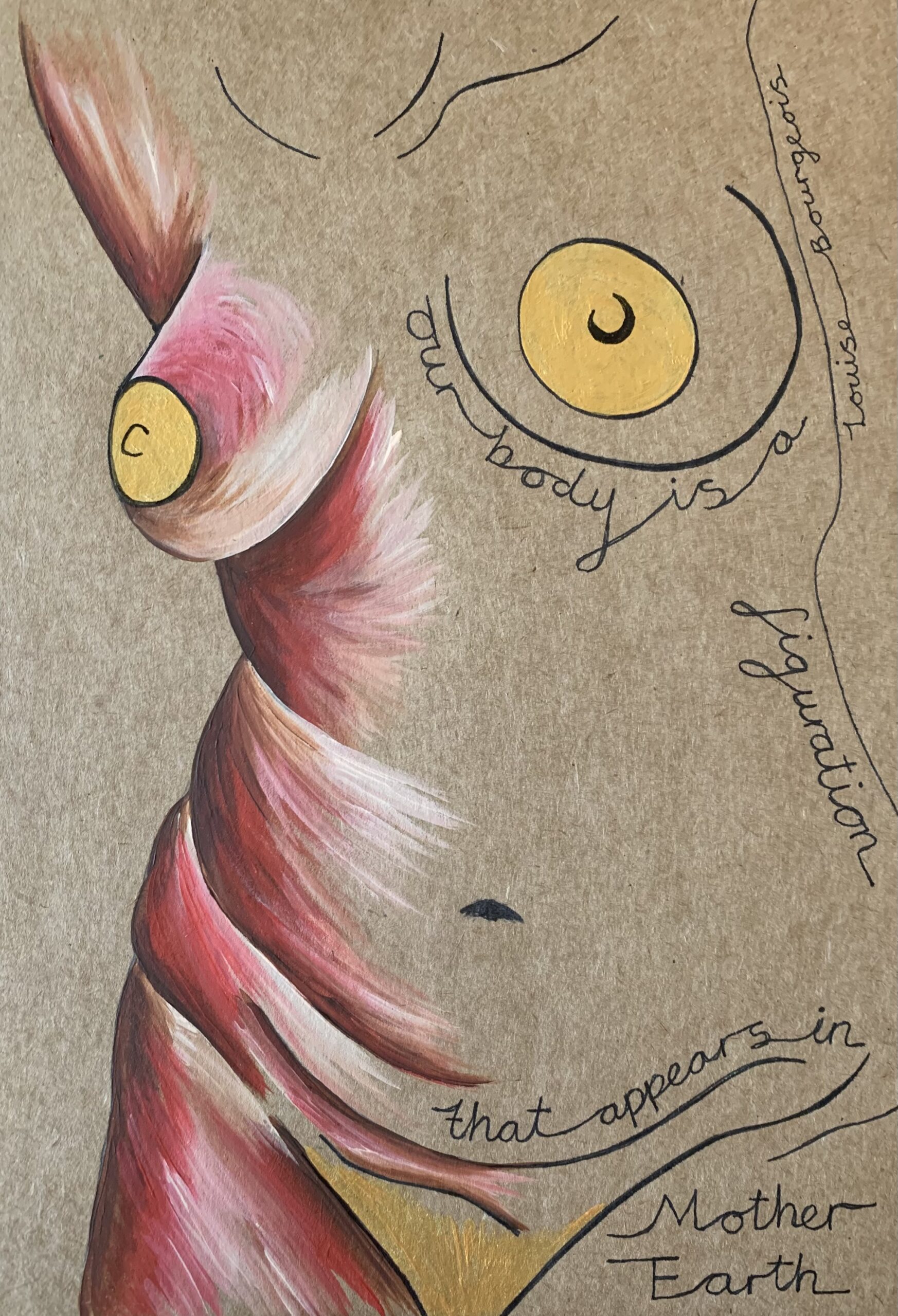

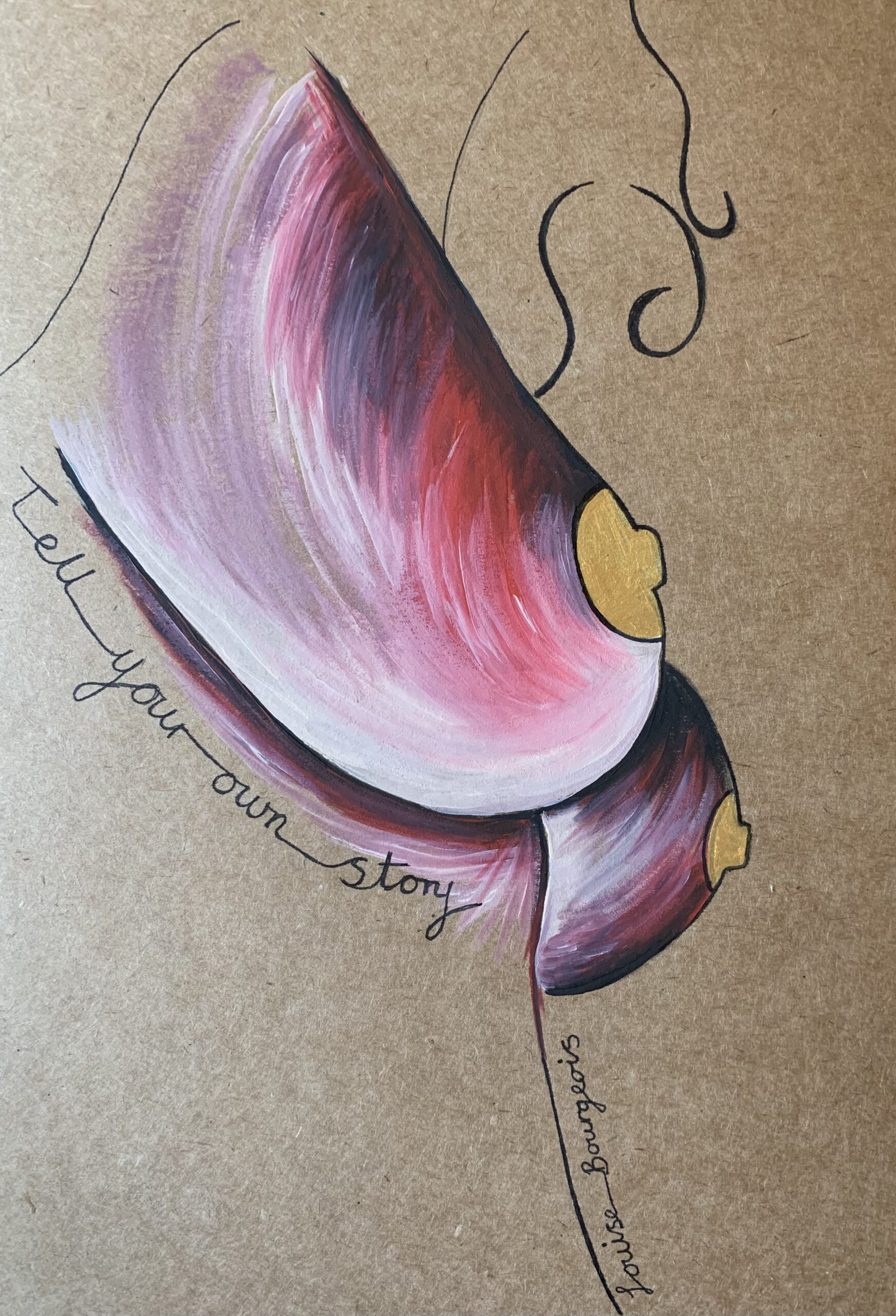

Louise Bourgeois

Louise Joséphine Bourgeois (1911 – 2010) was a French-American artist.

Bourgeois was born in 1911 in Paris to a family of tapestry weavers, and her first drawings were made to help her parents with tapestry restorations. She studied mathematics at the Sorbonne, but her mother's death, when Louise was just 22, prompted a change of focus to art. She evaded tuition fees by working in classes as a translator, and after graduating from the Sorbonne in 1935, she studied at various places including the École des Beaux-Arts and several academies and artist’s studios, including the studio of Fernand Léger. Her mother’s death, coupled with her father's serial unfaithfulness, were major influences in her predominantly autobiographical work.

In 1938, she began exhibiting at the Salon d'Automne and opened her own gallery next to her father's tapestry gallery, featuring artists such as Eugène Delacroix, Henri Matisse and Suzanne Valadon. In the same year, she met and married American art historian Robert Goldwater, a gallery visitor, and moved with him to New York City. She had three children in rapid succession and began moving in the city's art circles, exhibiting her Surrealist paintings and engravings.

Bourgeois had several solo shows throughout the 1940s and early 1950's, and developed her interest in sculpture, working mainly in wood. Her Femme Maison ('housewife') paintings and drawings, with the feminine form represented as architectural structures, reflect her transition into motherhood and American life, and the conflicts within female identity. Over the next decade, her interest in psychoanalysis pulled her away from her art, but in the 1960s, she began experimenting with latex, plaster, rubber, marble and bronze. However, whatever the medium and however real or surreal her style was, her work explored the same themes: jealousy, fear, abandonment and identity.

The 1970's saw her start teaching and become more socially and politically active, joining the Fight Censorship Group to defend the use of sexually explicit images in art. In 1982, at 70 years old, Bourgeois had a retrospective at The Museum of Modern Art and this made her bolder than ever.

Some of her best-known works were produced in the last two decades of her life, such as her monumental steel and bronze spiders, which were inspired by her mother as protector/ repairer/ weaver. She experimented widely with materials, including wire and even her old clothes, while also returning to her original mediums of drawing on paper and printmaking.

Bourgeois was chosen to represent the USA in the Venice Biennale in 1993 and died in 2010, at the age of 98.

“I am a searcher… searching for the missing piece.”

“Our body is a figuration that appears in Mother Earth.”

Tell your own story.”

Lydia Ruyle

Lydia Ruyle was born on the 4th of August 1935, in Denver, USA. In 1938, the family moved to Greeley, which became Ruyle’s lifetime home. She studied political science at the University of Colorado and, shortly after graduating in 1957, married Robert Ruyle. Once he had finished law school, they took their young family back to Greeley where she took up art, attaining her Master of Fine Arts in 1972.

While teaching Women’s Studies, Art History and Printmaking at the University of Colorado, her interest in women’s art and the Goddess culture grew. Her Goddess Icons appeared in a 1987 art exhibition, Better Homes & Goddesses, at the Loveland Museum and Gallery for National Women’s History Month.

The 90s saw her begin her Goddess Tours and YaYa Journeys, allowing women to share her love for women’s spirituality and travel with her to special, spiritual places around the world. She also campaigned for women’s rights and began creating her Goddess Banners. The initial 18 were made for a 1995 exhibition at the Celsus Library in Turkey, and over time, her collection grew to over 300; they embellished The Goddess Conference’s temple every year, honouring the Goddesses of each culture and place at sacred sites in 38 countries. They also were shown at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, and the United Nations World Conference on Women.

Ruyle’s first book, Goddess Icons, was published in 2002, and in 2010, the University of Colorado created the Lydia Ruyle Room of Women’s Art to continue her mission to teach. Her second and final book, Goddesses of the Americas, was published in 2016, and Ruyle died that same year. A documentary, Herstory: The Visionary Life of Lydia Ruyle and the Banners of the Divine Feminine, tells the story of her incredible artwork and research, and how her worldwide community came together to celebrate and honour her after her death.

“How did I find the Goddess? She called me and I listened.”

“And then all will live in harmony with each other and the earth.”

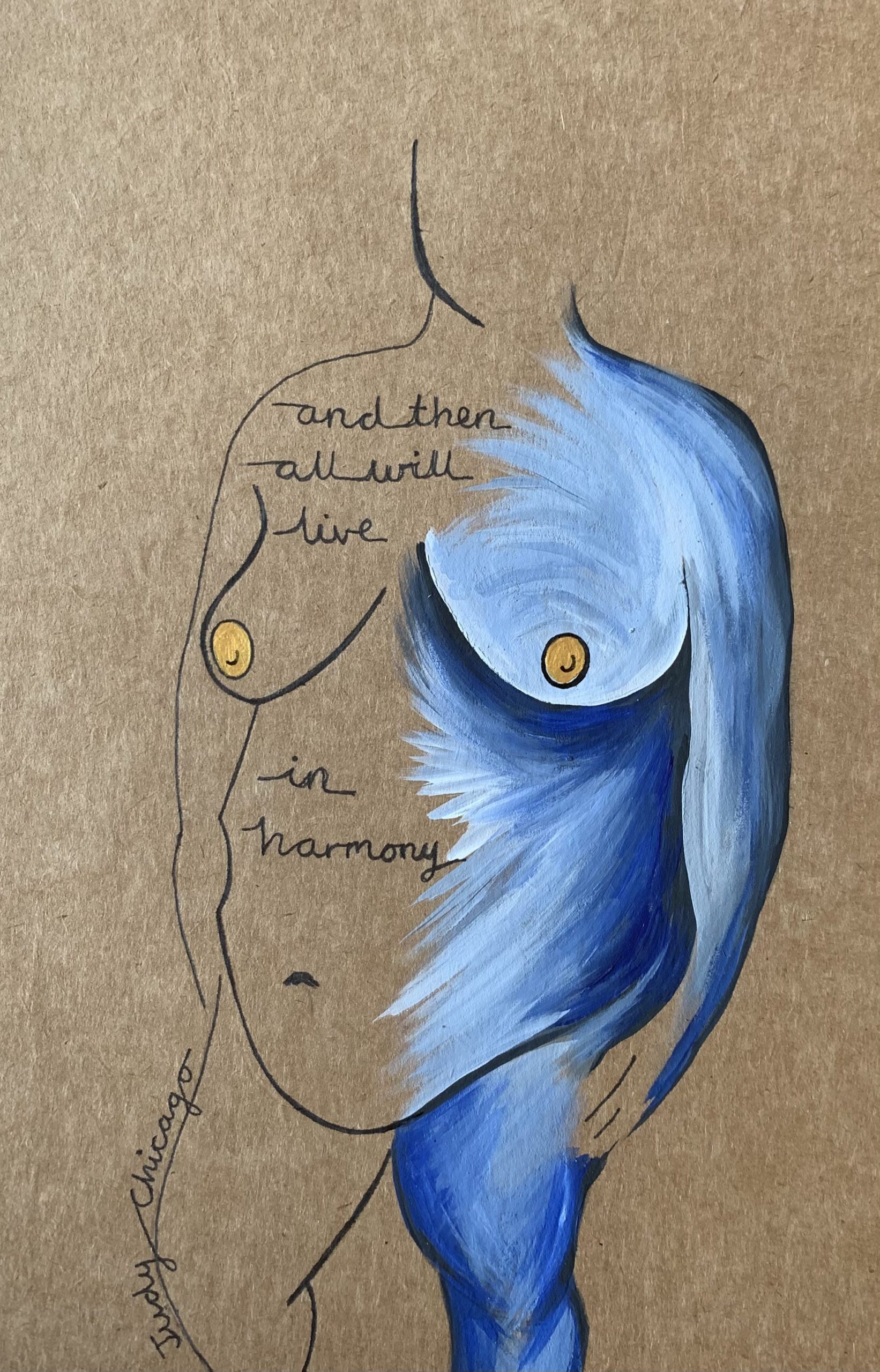

Judy Chicago

Judy Chicago is an American feminist artist, art educator, and writer.

Born Judy Cohen in Chicago in 1939, Chicago was focused on art from a very young age. She gained a Master’s Degree in painting and sculpture at the University of California in 1964. After losing her husband to a car accident in 1963, she remarried in 1969 but changed her name to Chicago rather than her husband’s name to break patriarchal naming traditions. Meanwhile, her art career flourished. She had her first solo exhibition in 1965, and her work gradually became more and more centred around female imagery and the growing women’s movement as the decade progressed.

In 1970, she launched a unique feminist, women-only art programme at California State University in Fresno with fellow artist Miriam Schapiro, later motiving it to the California Institute of Arts. The programme reflected her lifelong aim, which is to prevent and reverse the eradication of women’s achievements, and spawned Womanhouse: a woman’s art space for teaching, exhibition and discussion. However, unhappy with inequality at the Institute, she set up the Feminist Studio on a separate site among other creative feminist enterprises, which developed into the Woman's Building—the site became a hub for the feminist movement.

In 1974, she began work on the iconic piece The Dinner Party, collaborating with numerous craftswomen. Completed in 1979, this huge, triangular installation features a table with 39 elaborate settings for key female figures, including Sacagawea, Eleanor of Aquitaine, and Georgia O’Keeffe. Chicago wanted to highlight the breadth of women’s history and those crafts, such as needlework and pottery, long seen as predominantly women’s work and undervalued in art circles. Despite decades of controversy, rejections and even dismantlement, today, it’s permanently housed in the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum.

She has continued to mainly focus on producing large, mixed-media installations that require collaborative working and highlight the female experience. The Birth Project (1980–85) addressed the absence of birth imagery in art, while The Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light (1985–93) focused on the Holocaust and her identity as a Jewish woman. In The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction (2019), Chicago explored death from both a personal and species-wide viewpoint.

Chicago has also written several books, including volumes of autobiography, and continues to be involved in a variety of art and design projects, including fashion set design and glass-blowing. In 2021 the de Young Museum, San Francisco, held an exhibition of Chicago’s work, which it billed as her first major retrospective. She continues to be vocal in her challenge of male domination of art through the ages and champions crafts and art forms traditionally practised mostly by women.

Kat’s favourite Judy Chicago quotes:

“I am trying to make art that relates to the deepest and most mythic concerns of human kind and I believe that, at this moment of history, feminism is humanism.”

“Female deities were gradually overshadowed by or incorporated into the attributes of a number of male gods, then eclipsed by the ascendence of the single male deity that now dominates.”

“Historically, women have either been excluded from the process of creating the definitions of what is considered art or allowed to participate only if we accept and work within existing mainstream designations. If women have no real role as women in the process of defining art, then we are essentially prevented from helping to shape cultural symbols.”